The Mask of Melancholy: Why We Still Cling to the Sound of a Broken Heart

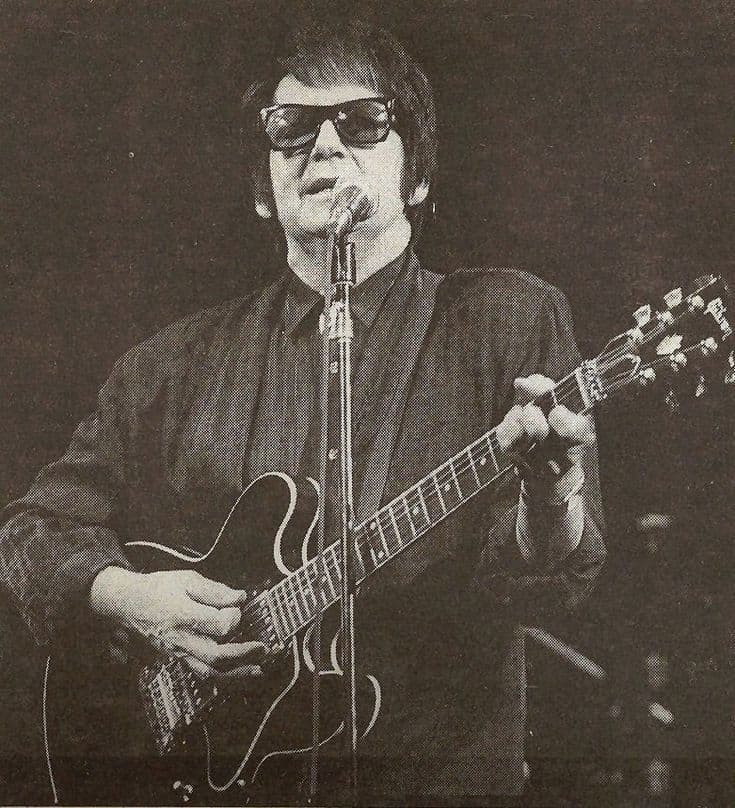

For those of us who came of age with the golden age of Rock and Roll—or perhaps just discovered its timeless echoes later in life—the name Roy Orbison conjures a very specific, beautiful sorrow. He was the master of operatic tragedy in three minutes, the man behind the dark glasses whose voice could ascend from a tender baritone to a near-impossible falsetto that perfectly captured the shattering experience of loss. When he took on the classic The Platters hit, “The Great Pretender”, in 1962, he didn’t merely cover it; he took the original doo-wop lament and imbued it with his own unique, trembling gravitas, transforming it into a signature piece of his early 1960s repertoire.

The original version of “The Great Pretender” was a colossal success for The Platters, written by their manager, Buck Ram, who famously penned the song in a hotel washroom stall to meet a tight deadline. The Platters’ single, released in late 1955, shot straight to No. 1 on the Billboard Top 100 chart in early 1956, becoming an immediate defining song of the era. However, Roy Orbison‘s reinterpretation, recorded for his 1962 album, Crying, did not achieve the same breakout chart success as a standalone single. Instead, it served as a cornerstone track on an essential album that cemented his image as the “Big O” and included other monumental hits like the titular track, “Crying.” For many listeners, particularly those who embraced Orbison‘s distinct brand of dramatic rock-and-roll balladry, his version became the definitive one, a testament to its enduring power outside of simple chart rankings.

The story behind the song itself is as simple as it is universally felt, which is perhaps why it continues to resonate. Its core meaning is an exploration of solitary grief and the social facade we construct to hide it. The narrator is a heartbroken man who has been left “to grieve all alone,” yet who must “go on pretending” that his life is perfectly fine. He is a “clown,” “just laughin’ and gay,” desperately trying to convince the world, and perhaps himself, that he is “doing well” after a devastating breakup. This is the “great pretender”—the one who makes believe so effectively that no one can tell the truth of his profound loneliness.

The power of Orbison‘s delivery is what elevates this song from a simple doo-wop number to a theatrical masterpiece. Recorded in Nashville with his customary team of stellar session musicians, the instrumentation swells and recedes with his voice. Where The Platters‘ Tony Williams brought a smooth, soulful ache to the lyric, Orbison brings a controlled, yet palpable, tension. His vibrato on lines like, “Too real when I feel what my heart can’t conceal,” is the sound of a man’s carefully constructed mask finally cracking, a moment of exquisite vulnerability that instantly tugs at the memory of our own private heartbreaks.

For older generations, this song is not just a relic of the early ’60s; it’s an emotional echo of a time when men were often expected to silently bear their emotional wounds. Orbison’s dark suit, his ever-present shades, and the high-flying, almost ghostly quality of his singing gave voice to the sorrow that had to be hidden from the daylight world. It’s a reflective piece, perfect for those quiet, late-night hours when the charade has ended and we are left only with the mirror, seeing the truth of the “great pretender” staring back. It reminds us that sometimes, the greatest performance we ever give is the one we put on every morning just to face the day.