The weight of grief laid bare in one timeless cry

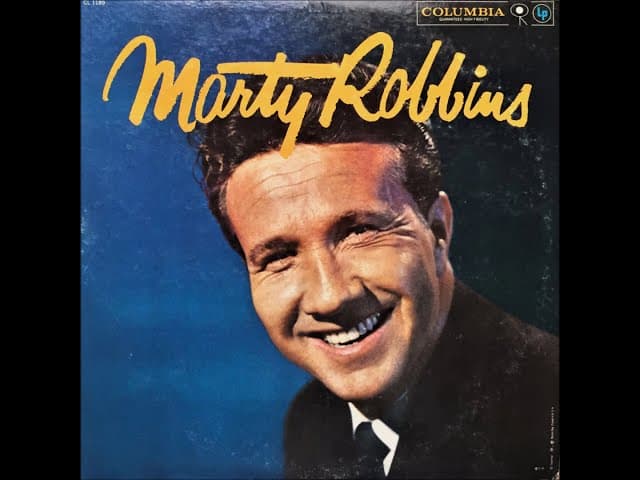

From the opening chord of “YOU GAVE ME A MOUNTAIN”, the listener is drawn into a voice that knows sorrow as intimately as it knows hope. Penned by the great Marty Robbins and featured on his 1969 album It’s a Sin, the song stands as a towering monument of personal reckoning, even though Robbins’s own version was not released as a major single. In the hands of Frankie Laine, the most commercially visible ascent of the song reached No. 24 on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 and held in the Top 40 for seven weeks.

But the true summit of the song lies not in chart numbers—it lies in Robbins’s unflinching confession of struggle, undoing, and survival.

Behind the simple metaphor—the mountain that has been given—walls of pain rise. Robbins crafts a narrative not of triumph from no hardship, but of dignity carried through relentless weight. The lyric “my woman got tired of the hardship, tired of the grief and the strife” evokes a domestic life stretched thin, the quiet despair of giving and never receiving equivalent return. The mountain then becomes not only an obstacle, but a catalogue of losses: a mother gone, a father absent, love gone wandering. The song’s structure—verse after verse of obstacles, culminating in the stark concession “a mountain you know I may never climb”—resonates because it refuses to offer easy endings.

Musically, Robbins frames the message with a sober arrangement. The melody moves upward as if scaling, note by note, the titular mountain. His baritone voice—rich, textured, and unadorned—carries each line with the steely emotion of someone who has known both the weight and the wonder of hope. In that way, the song becomes both a lament and a quiet hymn: the lament for what’s lost, the hymn for what endures.

Culturally, “You Gave Me a Mountain” occupies a unique space in Robbins’s catalog. Known for his western ballads, cowboy epics, and crisp pop-crossover songs, here Robbins turns inward, choosing raw emotional terrain over sleight of style or iconic landscape. The fact that the song has been covered by many—with Elvis Presley among them, elevating the piece into a broader arena of universal resonance—speaks to its power.

What remains most compelling, decades later, is how the song invites the listener to become the climber. To hear Robbins not merely as singer but as fellow pilgrim trudging up his mountain. There is no glory in this climb, but there is grit—and in that grit lies redemption. The song doesn’t promise victory; it recognizes the mountain, accepts its height, and chooses to keep going anyway.

In listening, we bear witness. In reflecting, we understand. And in remembering Robbins’s artistry, we honour a voice that, when handed the mountain, still refused to turn away.