A tender, heartfelt cover that transformed personal tragedy into a communal hymn of enduring loss and hope.

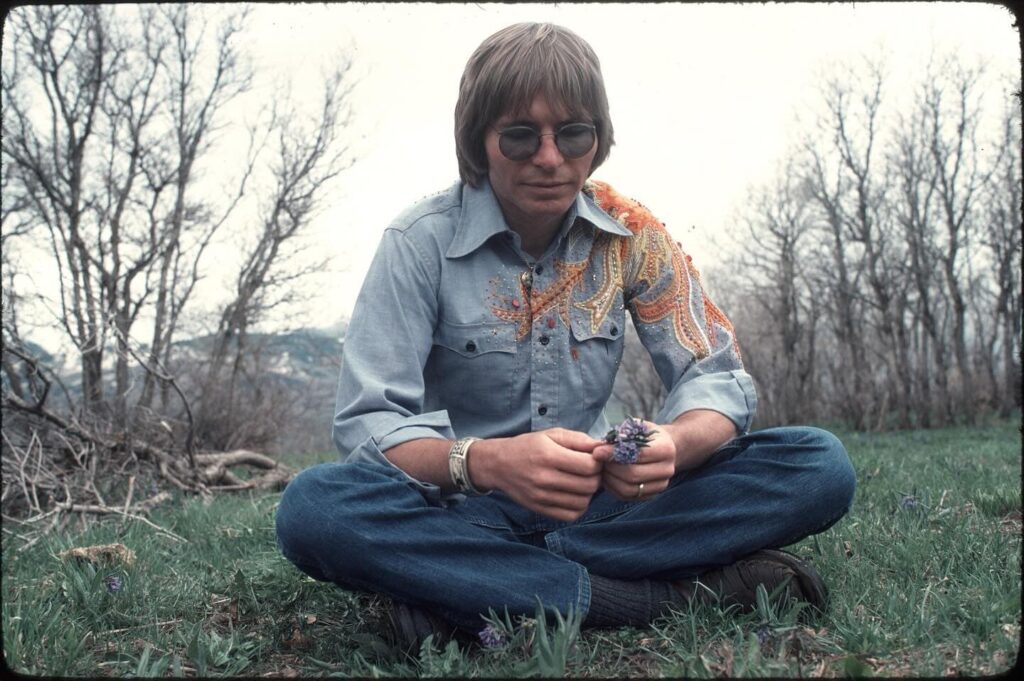

For those of us who came of age with the emerging singer-songwriter movement of the late 60s and early 70s, certain songs are more than just tunes; they are milestones marking the passage of time and the universal aches of the soul. John Denver’s rendition of “Fire and Rain,” released on his breakthrough 1971 album, Poems, Prayers & Promises, is one such classic.

It’s crucial to acknowledge from the outset that this profoundly moving song was penned by the brilliant James Taylor. Taylor’s original version, a cornerstone of his 1970 album Sweet Baby James, was the smash hit that catapulted the genre to the fore, peaking at Number 3 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. While John Denver’s version was a key track on the album that gave us the ubiquitous “Take Me Home, Country Roads,” his take on “Fire and Rain” was an album cut and, unlike Taylor’s original, did not chart as a single. Yet, in the quiet, reflective canyons of memory, Denver’s cover holds a special, cherished place for many, including his dedicated fans and those who gravitated to his sunnier, folk-pop arrangements.

The Story Behind the Tears and the Tune

The real heart of this song, regardless of the performer, lies in its unflinching honesty about loss and addiction. James Taylor wrote the song as a young man grappling with overwhelming personal turmoil, an experience he masterfully distilled into three cryptic, devastating verses. The first verse, which opens with the poignant line, “Just yesterday morning, they let me know you were gone,” refers to the tragic suicide of Suzanne Schnerr, a childhood friend whose death was withheld from him for months by well-meaning friends who feared it would derail his early recording career in London. The sense of disorientation and delayed grief is palpable in the line, “I walked out this morning and I wrote down this song, I just can’t remember who to send it to.”

The following verses pull back the curtain on Taylor’s own struggles: his time spent at a psychiatric institution, and his crippling heroin addiction, referenced in the desperate plea, “Won’t you look down upon me, Jesus? You gotta help me make a stand, you just got to see me through another day.” Finally, the seemingly gentle lines, “Sweet dreams and Flying Machines in pieces on the ground,” refer not to a plane crash, as was a common rumor, but to the collapse of his early band, The Flying Machine.

The Meaning in Denver’s Hands

While James Taylor’s delivery is raw, hushed, and deeply confessional, John Denver’s interpretation shifts the emotional center. Where Taylor’s voice is a fragile whisper of pain, Denver’s is a clearer, more open-throated lament. His version, produced by Milton Okun, features a slightly brighter arrangement, utilizing the gentle pluck of acoustic guitar, piano played by Frank Owens, and the melancholic depth of a double bass. This subtle shift allows the song’s central theme of enduring, cyclical pain to resonate with a broader, more universal resonance. The “fire and rain” of the chorus—often interpreted as the extremes of good times and bad times, or the burning of fever and the wash of tears—becomes, in Denver’s hands, a shared acknowledgment of the human condition.

For us, listening to Denver’s voice on this track today is like flipping through an old photo album. We remember a time when folk music wasn’t just entertainment, but a mirror reflecting life’s complexities back at us with gentle compassion. Denver took a painful piece of another man’s heart and, without compromising its integrity, turned it into a comforting embrace, reminding us that even in the loneliest times, we are not truly alone in our fire and our rain. This recording is a perfect example of a respectful cover adding a new, necessary layer of warmth and hope to a timeless, somber masterpiece.