A Solemn, Upbeat Prophecy of the End Times and the Final Reckoning, Spoken by the Man in Black

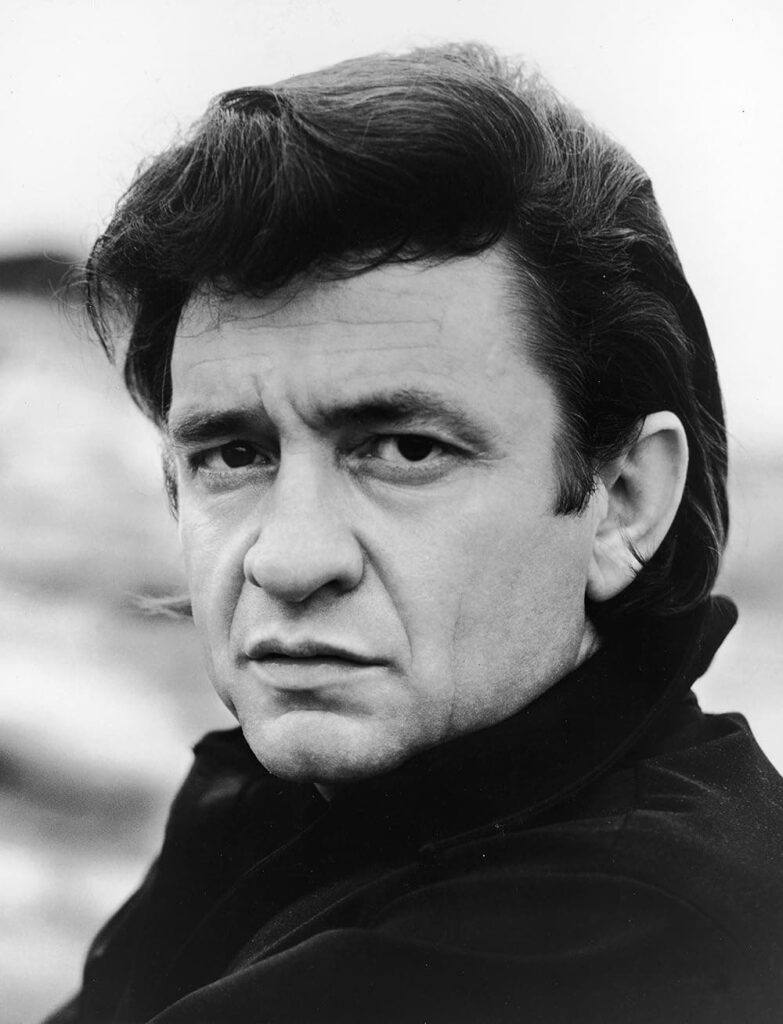

There are songs that simply echo through a career, and then there are those that act as a profound, final testament, a perfect summation of a lifetime of faith, sin, and redemption. “The Man Comes Around,” the title track from Johnny Cash’s 2002 album, American IV: The Man Comes Around, is firmly the latter. Released in the twilight of his monumental life, just shy of a year before his passing, the song carries an overwhelming weight of portent and acceptance.

Though the song itself was not released as a commercial single and thus did not chart on the primary Billboard Hot 100 or Country Singles charts, its parent album was an unqualified triumph, achieving a Platinum certification and peaking at Number 22 on the overall Billboard 200 chart and Number 2 on the Top Country Albums chart in late 2002/early 2003. This commercial success, late in a legendary career, confirmed that the world was still listening intently to the Man in Black’s voice—a voice now deepened by age and worn smooth by hardship, making his prophetic words all the more arresting.

The Vision and the Meaning

The story behind the song is as evocative as the lyrics themselves. The inspiration struck Cash years before the recording, stemming from a vivid dream he had while visiting England. In this dream, he saw Queen Elizabeth II, who compared him to “a thorn tree in a whirlwind.” Haunted by the image, he later began searching the Scriptures, eventually finding a similar phrase and a wealth of related imagery in the Book of Revelation. This deeply personal vision, filtered through his lifelong Christian faith, became the backbone of a song that would take him nine months to write—an unprecedented period for the typically rapid-fire songwriter. He admitted to writing 25 or 30 verses before settling on the chilling final composition.

The meaning of “The Man Comes Around” is rooted in the Biblical Book of Revelation, specifically focusing on the Second Coming of Christ and the inevitable Judgment Day. It is a spiritual, apocalyptic vision delivered not with fire and brimstone terror, but with a kind of jaunty, resolute certainty. Cash, a man who knew the shadows of life intimately, had reached a point of serene acceptance, transforming the end of the world into a reckoning that is both fearful for the wicked and a glorious homecoming for the faithful. The opening, with the spoken-word excerpt from Revelation 6 describing the Four Horsemen, immediately sets the stage for a grand, final theatre.

A Nod to the Past, a Look to the Future

The brilliance lies in how Cash weaves together the ancient scriptural passages with his own plainspoken, country-folk poetry. He blends direct references—the “white horse,” the “golden crowns” cast down before the throne (Revelation 4:10), the wise virgins trimming their wicks (Matthew 25:1–13)—with his own stark, unforgettable pronouncements: “There’s a man goin’ ’round takin’ names / An’ he decides who to free and who to blame.” The voice is not that of a distant preacher, but of a trusted witness, someone who has walked the line and seen the signs.

For those of us who grew up listening to the rough honesty of Johnny Cash, this final chapter, guided by producer Rick Rubin, was a profound gift. It was the sound of a great artist making peace, not just with his audience, but with his God. The sparse, acoustic arrangement and the steady, marching beat create an almost hymn-like quality, suggesting that this cosmic event is less a surprise catastrophe and more a long-foretold conclusion. When he quotes the chilling finality of Revelation 22:11, “Whoever is unjust, let him be unjust still. Whoever is righteous, let him be righteous still. Whoever is filthy, let him be filthy still,” it’s a late-game reminder that there is a point of no return. The song is not a plea for change; it is the sound of the clock running out, delivered by a man who sounds utterly ready for the Alpha and Omega’s Kingdom Come. It’s a gorgeous, haunting reflection on mortality that feels less like an ending and more like a great, assured “Amen.”