A Heartbreaking Ballad of Devotion: The Story of a Mother’s Desperate, Unavailing Visit to Her Imprisoned Child.

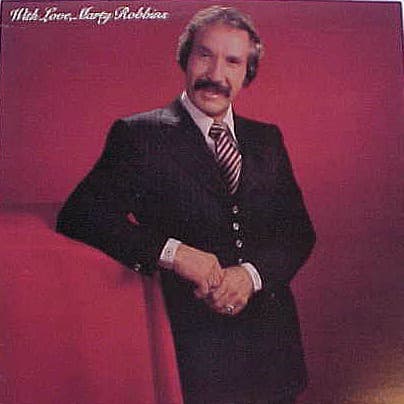

There are certain songs, aren’t there, that feel less like a piece of music and more like a faded photograph—a moment in time captured with an ache of the heart that only deepens with age. Such is the enduring power of Marty Robbins’ recording of “I’m Just Here To Get My Baby Out Of Jail.” This wasn’t one of the chart-topping, genre-defining hits like “El Paso” that solidified Robbins’ legendary status; in fact, the song itself, written by Karl Davis and Harty Taylor (often credited as Tex Atchison) in the 1930s, is an old country standard. Marty Robbins’ rendition, which appeared on his 1981 album, The Legend, didn’t have a single release and therefore did not register a position on the major Billboard country or pop charts at the time, arriving late in his prolific career. Yet, its absence from the charts only underscores its deep, foundational place within the cannon of country storytelling—a testament to its timeless, tear-in-your-beer authenticity.

The Story and Meaning: A Visit to the Stone Walls

The soul of this track lies in its profoundly simple, yet utterly devastating, narrative. The song is a first-person account, a conversation overheard, perhaps, at the cold, forbidding entrance of a penitentiary. The speaker is a devoted, aging mother who has traveled a great distance, laden with a basket of home-cooked comfort, only to be turned away at the prison gate. “I’m Just Here To Get My Baby Out Of Jail” is her heartbreaking plea, her single-minded justification for being there. It’s a lyric that captures the raw, unfiltered essence of unconditional maternal love—a bond that the narrator believes should be more powerful than any legal decree or barred window.

The “baby” in question is not an infant, but her grown son, now a prisoner. The meaning, therefore, is rooted in the universal truth that a mother’s child never truly outgrows their need for her, nor does she cease to see him through the filter of his youth and innocence. She’s not there to argue the legalities; she simply can’t comprehend why her son, her flesh and blood, is trapped behind the stone walls. In her eyes, the simple act of her physical presence, her love, and the basket of food should be enough to secure his release. This disconnect between a mother’s fervent wish and the harsh reality of the penal system is what gives the ballad its piercing, melancholy quality.

A Nostalgic Touch in the Twilight of a Career

Marty Robbins was a master storyteller, a musical troubadour who could transport you to the dusty plains of the Wild West or the tear-stained porch of a troubled home. His decision to record this song later in his career, on The Legend, feels like a reflective nod to the deep country roots he always honored, even as he crossed over to pop success. While earlier recordings by acts like the Blue Sky Boys and Hank Snow had cemented the song’s status as a country standard, Robbins’ smooth, resonant baritone brings a certain weary gravitas to the role of the devoted mother’s advocate—the voice that hears her tragedy.

Listening to Marty Robbins sing this today is to step back into an era when a song didn’t need a massive production or a slick music video to break your heart. It relied on a simple melody and a story so human that it resonated in every farmhouse and city apartment where a mother worried for her child. It’s a bittersweet reminder of a time when the greatest drama was often found not in fiction, but in the ordinary struggles of everyday people—a theme Robbins always championed. It evokes a simpler, perhaps tougher time, where devotion was paramount and heartache was just a chord away.

The simplicity of the song—just a few verses and a chorus—is its strength, leaving a lingering, poignant silence after the final chord fades. It’s a classic country tear-jerker that, like all great art, taps into the timeless, unbreakable thread of family devotion against insurmountable odds.