The Barbed Wire and the Bloom: A Timeless Ode to Lost Innocence and Unreachable Love

In the vast, resonant canon of country music, certain songs stand not merely as popular hits, but as deeply etched emotional landmarks, connecting generations through shared feelings of longing and despair. Among these treasured reflections is Marty Robbins‘ masterful 1956 recording of “The Convict And The Rose,” a track that, while not a chart-topping single in the modern sense of the word, possesses a far greater currency: a timeless, soulful weight that cemented its place in the lore of country balladry.

While this somber, compelling number did not register on the major Billboard country or pop charts of its time—it was released as a B-side or an album track, and chart data for all B-sides of that era is sparse—its power was felt on the radio waves and in the homes of a nation still deeply connected to storytelling through song. Robbins recorded this beautiful, classic lament on September 4, 1956, and it was a staple on his extended play (EP) releases, notably appearing on the “Marty Sings The Letter Edged In Black” EP. The song itself is a revival of a much older composition, originally written by the prolific songwriting duo of Robert King and Ballard MacDonald (sometimes credited to the pseudonym Betty Chapin) and dating back to the early 20th century. Robbins took this fragile relic of a bygone age—a piece that speaks to the very origins of American popular and folk music—and infused it with his distinctive, earnest vocal delivery, making it profoundly his own.

The story behind the song is one of pure, distilled tragedy, a vignette set within the harsh, unforgiving walls of a prison. It recounts the final, haunting vision of a man—a convict—shortly before his execution. As he walks his last mile, his eye catches a single, delicate rose growing near the dreary confines of the prison wall. This isn’t just a flower; it is an ephemeral symbol of everything he has lost—freedom, innocence, and the memory of the woman he loved. The rose, with its intoxicating beauty and stark contrast to the gray stone and cold steel, instantly reminds him of his sweetheart. The lyric, often delivered with Robbins’ heartbreaking sincerity, captures this moment of profound, painful clarity: the rose is sweet, beautiful, and alive, while the man is none of those things.

The profound meaning of “The Convict And The Rose” rests on this core juxtaposition. It is a meditation on the unbridgeable chasm between guilt and redemption, between the vibrant world of memory and the barren existence of a condemned man. For older listeners, particularly those who grew up listening to the stark, morality-driven narratives of classic country and folk, the song evokes a time when songs didn’t offer easy answers, but instead forced a deep reflection on life’s harsher truths. The rose is unreachable beauty, separated from the convict by the literal wall of his prison and the metaphorical wall of his crime. It highlights the ultimate irony of his final moments: finding such a perfect reflection of pure love just before he faces the absolute finality of his punishment.

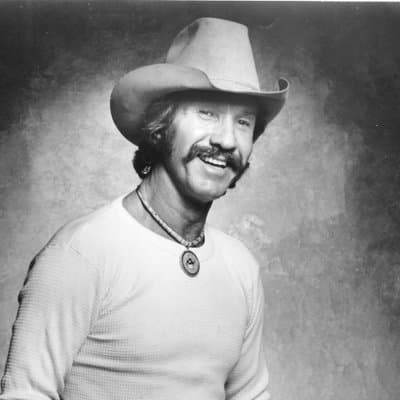

Marty Robbins’ genius lay in his ability to inhabit these characters, whether they were gunfighters in the dusty West or a broken man in a prison cell. He was a master storyteller, and his rendition of this song—sparse in instrumentation, rich in emotion—carries the weight of a heavy heart. Hearing it today is like opening a brittle, yellowed letter from a time when life felt harder, simpler, and the songs, perhaps, had deeper roots in the human condition. It’s a lullaby of sorrow, a beautiful and devastating piece that reminds us of the fragility of life and the endurance of love, even unto death.