A haunting, nostalgic plea from a wandering musician to his guitar, to play a song that can take him back home, even if only in his memory.

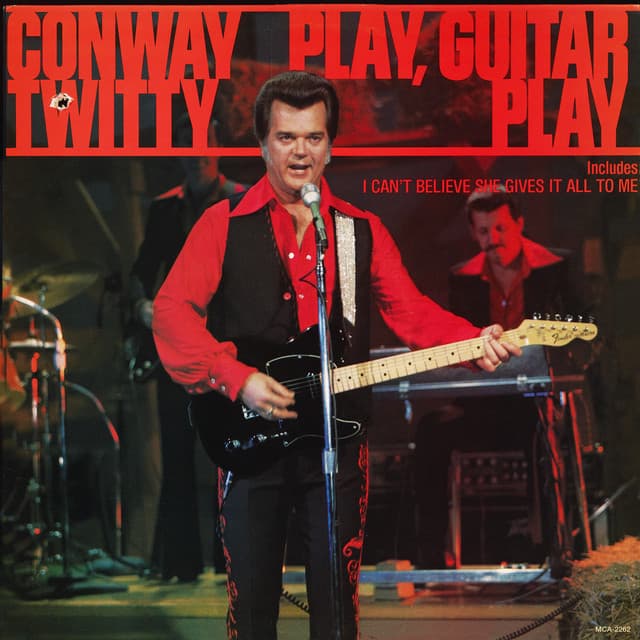

The year was 1977, and the airwaves were once again dominated by the inimitable baritone of Conway Twitty. On February 7th, MCA Records released what would become one of the most lyrically complex and deeply felt recordings of his career: the self-penned single, “Play Guitar Play.” This track, which also served as the title cut for his 1977 album, swiftly connected with a massive audience. It continued Twitty’s incredible chart dominance, securing his 19th trip to the summit of the country charts where it enjoyed one week at number one and spent a total of 13 weeks on the Billboard Hot Country Songs chart. This commercial success only tells part of the story, though. The real magic of “Play Guitar Play” lies in its wrenching narrative, a sharp turn from Twitty’s usual repertoire of sultry, romantic ballads.

The Ballad of the Good Boy Gone Wrong

To truly appreciate the song, one must understand the emotional depth of its lyrics. Conway Twitty—born Harold Lloyd Jenkins—was a master of writing songs that felt intensely personal, and this one is a classic example of that gift. “Play Guitar Play” is essentially a desperate, intimate conversation between a traveling musician and his most trusted companion: his guitar. The man is a fugitive from his own life, a classic country archetype, having run away from his childhood home in the fields of the South after committing an “awful thing.”

The opening lines are a nostalgic ache: “Play, guitar play / Take me back to yesterday / Let me see cotton growing in the fields.” This is not just a request for a tune; it’s a plea for sonic time travel. The music is his only way back to the innocence he lost, to the sound of his “mamma callin’” and the vision of home. The core tragedy is immediately laid bare: “Down the road he’s a comin’ home / But they know I never will.” He is forever separated from the place and people he loves by the unnamed “awful thing I done.”

The “story behind it” isn’t based on a documented event in Twitty’s own life—a life known for its stability and dedication to family, which is a key part of his unique appeal—but it draws from the universal themes of regret, running, and the search for redemption that resonate so strongly with working-class America. It is a portrait of a man haunted by the irreversible mistake of his youth, who can only find temporary solace in the music he plays for strangers in far-off towns. The guitar isn’t just an instrument; it’s a confessional booth, a time machine, and the very symbol of the rambling, lonely road he chose, or was forced, to take.

The Meaning of the Endless Road

The true meaning of the song deepens as the narrative progresses. The musician asks his guitar to “Help me through another day / Help me make another dollar, before I go.” This reveals a cycle of endless wandering, where every performance is just a means to survive one more day on the run. The most chilling part comes when he wonders if his audience—the “another crowd” in the “another town”—can “read between the lines in my song” as he sings about “a good boy that’s went wrong.”

This is the genius of Twitty’s songwriting: the song itself becomes the narrator’s only link to his past and his true identity. He is singing his own biography to an unwitting audience. The true “game” is the life he is now living—a masquerade as a carefree musician, when he is, in fact, a soul in turmoil.

“Play Guitar Play” stands out in Conway Twitty’s discography for its serious, almost somber mood, relying less on the famous “bedroom growl” and more on a raw, heartfelt delivery. The sophisticated guitar arrangement (recorded, as was so much classic country, at Bradley’s Barn in Mount Juliet, Tennessee) echoes the very instrument to which the narrator is pleading, reinforcing the intimacy and desperation of the moment. For those of us who grew up listening to Twitty’s music, this song is a stark, unforgettable reminder that even the biggest stars sing about the small, deep hurts that never truly heal, carrying us all back to a time when a simple three-minute country song could feel like reading someone’s entire, tragic diary. It’s a tear in the eye, a lump in the throat, and a perfect piece of melancholy country gold.