The Long, Hard Road to the Top: The Price of Unrequited Devotion

The enduring meaning of the quiet bystander who will accept a broken heart just for a chance.

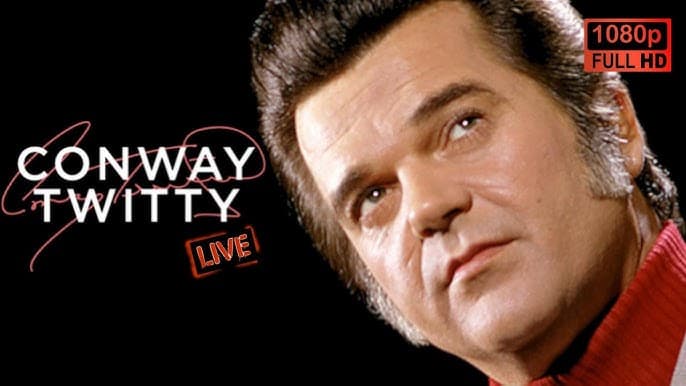

There are moments in music history that signal a monumental shift—not a sudden, flashy explosion, but a deep, foundational tremor. For the legendary Conway Twitty, that moment arrived in 1968 with the single that truly launched his reign in country music, “Next In Line.”

For those of us who remember the music of the late 1960s, the name Conway Twitty first conjured images of slicked-back rock and roll and the pop smash “It’s Only Make Believe.” But by 1968, Twitty was fully immersed in the Nashville sound, and this track, released in August of that year, was the ultimate validation of that move. “Next In Line” was his sixth single on the country charts, and it proved to be the magic key: it roared to the top, becoming Conway Twitty’s first-ever No. 1 hit on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart, where it spent a week at the peak position and a total of 13 weeks in the Top 40.

The success of “Next In Line” didn’t just mark a personal victory for Twitty; it ignited a chart-topping run that is, quite frankly, astonishing. It was the first domino in a breathtaking cascade that would see Twitty amass a record-setting fifty-five No. 1 hits over the course of his career—a feat that speaks volumes about his connection to the audience.

The story behind this song is less about the man singing it and more about the songwriters, Wayne Kemp and Curtis Wayne, who crafted a perfect country narrative: unrequited love observed from the shadows of a honky-tonk. The track, produced by the great Owen Bradley, showcases a raw, hard-country sound that contrasts beautifully with Twitty‘s already evolving vocal style. The music is sparse, dominated by a crying steel guitar and a rhythm section that keeps a quiet, steady beat, leaving the listener nowhere to hide from the heart of the lyric.

The meaning of “Next In Line” is a painful meditation on devotion that borders on desperation. The narrator sits, watching the woman he loves—the one who truly owns his heart—as she drowns her sorrows, heartbroken over another man. It is a portrait of quiet, unconditional willingness. He sees her tears, he knows her pain, and he knows why she is in that miserable state—but he still holds onto a thread of hope, however slim. The lines, “If she should change her mind / Give up the music and the wine / I’ll be standing by to be the next in line,” are the devastating core of the song. It’s an admission that he is prepared to be the permanent second choice, the emotional understudy, simply for the chance to dry her tears and maybe, just maybe, be loved in return.

For older listeners who have lived through the dizzying complexity of relationships, this song strikes a familiar, melancholic chord. It evokes the memory of sitting in a dimly lit corner, nursing a drink, while the object of your affection is fixated on a ghost or a mistake. It is the understanding that true, enduring devotion often means accepting less than you deserve, a choice Conway Twitty sings with a profound, world-weary empathy that was already his trademark. It is a masterclass in emotional restraint, delivering a heavy dose of heartache with the gentlest of voices, proving that sometimes, the most enduring country stories are those about the quiet heroes of unselfish, unshakeable love.