The Comfort in the Neon Glow: A Timeless Tale of Desperate Return

There are certain songs that, the moment the needle drops or the opening notes drift through the air, instantly transport you back to a specific time, a feeling, a whole era. For those of us who came of age in the 1970s, or whose hearts were broken and mended by the pure, unvarnished emotion of classic Country music, Conway Twitty’s “There’s A Honky Tonk Angel (Who’ll Take Me Back In)” is one of those indelible moments. Released in January 1974, this masterwork of heartbreak and weary resignation quickly ascended the charts, securing its place in history as Twitty’s 10th solo number-one hit on the U.S. Billboard Hot Country Singles chart, a position it held for a memorable week amidst its 12-week chart run. The song became the cornerstone—and title track—of his 1974 album, Honky Tonk Angel.

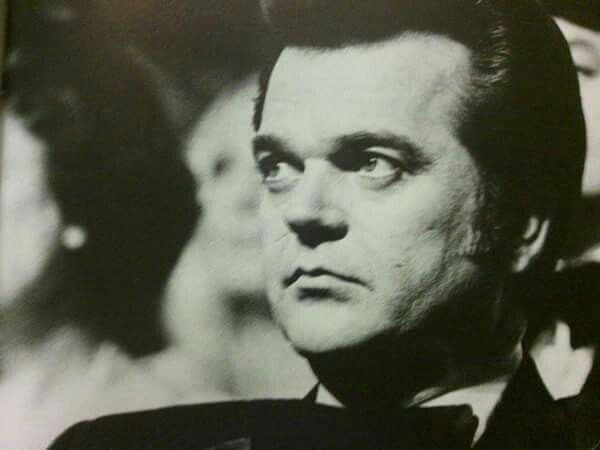

Penned by the gifted songwriting team of Troy Seals and Denny Rice, the song isn’t a celebration of carefree living; it is a profound and painfully honest admission of failure, wrapped in a blanket of neon-lit nostalgia. The music industry in the early 70s was a hotbed of changing tastes, but Conway Twitty—the man who could convey more sorrow and passion in a single, perfectly timed growl than most singers could in an entire album—remained the undisputed king of the country ballad. Produced by the legendary Owen Bradley at Bradley’s Barn in Mount Juliet, Tennessee, the recording captures that distinctive, lush Twitty sound, allowing his deep, resonant vocal performance to shine through every syllable.

The story laid bare in the lyrics is tragically simple, a narrative that resonated deeply with the older, more reflective listener. It centers on a man facing the cold, hard truth of a failed primary relationship—one that has withered into a loveless formality: “When was the last time you kissed me / And I don’t mean a touch now and then / It’s been a long time since you felt like my woman / And even longer since I felt like your man.” The air has been let out of the balloon, the pretense is exhausting, and he forces the painful conversation, recognizing the unspoken reality that one of them has found love elsewhere.

But the true, aching core of the song—its timeless meaning—lies in the figure of the Honky Tonk Angel. This isn’t a conventional “other woman.” She is a symbol of unconditional, non-judgmental acceptance. She represents a sanctuary from the sterile, demanding disappointment of his current life. He knows, with a certainty bordering on desperation, that if his current relationship ends, he has a refuge: “Well, there’s a Honky Tonk Angel who’ll take me back in.” The “Honky Tonk Angel,” in the vernacular of the time, often referred to a woman working in the bars, perhaps a prostitute or simply an emotionally available soul who understood the weary traveler and the fleeting comfort they sought. She doesn’t ask for promises; she accepts his brokenness without question. The angel of the song is the emotional safe harbor that society’s “respectable” relationships couldn’t provide. It’s a beautifully melancholic commentary on how sometimes, the most profound human connection is found in the places polite society is taught to scorn. Twitty’s delivery, dripping with sorrow, isn’t boastful; it’s the sound of a man who knows he’s making a lateral move from one kind of pain to another, yet choosing the one where he feels genuinely seen, if only for a night. It’s a song of profound vulnerability, making it one of the most resonant numbers of his golden era.