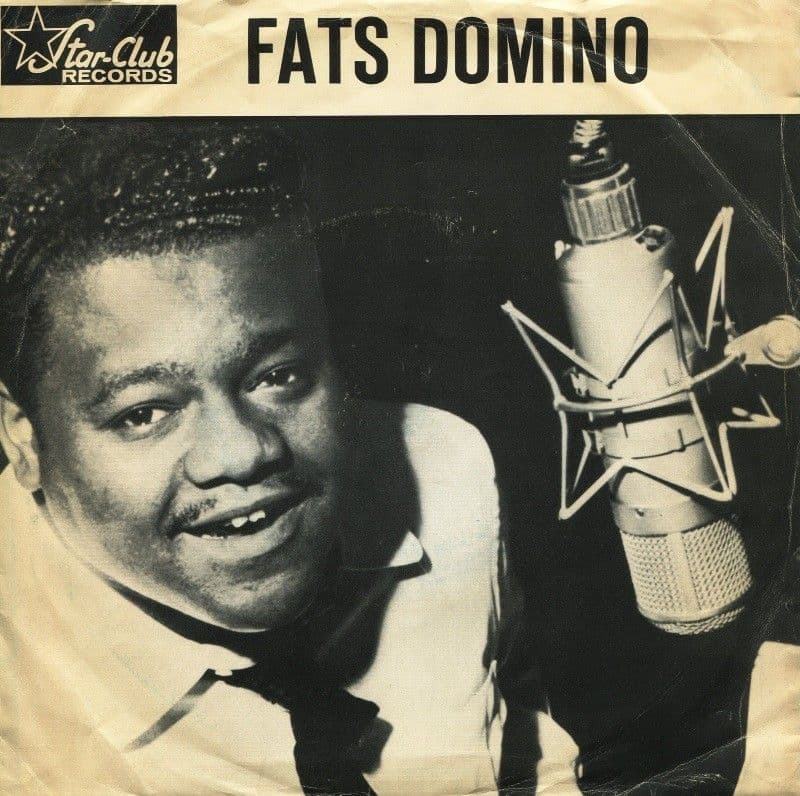

A Boogie-Woogie Pilgrimage to the Swanee: Fats Domino’s Celebration of Piano Spirit

“Swanee River Hop”, by Fats Domino, is a joyous, pounding instrumental that captures the pure exhilaration of New Orleans piano; though it wasn’t released as a major charting single, it remains one of Domino’s most electrifying showcases on the 1956 studio album Rock and Rollin’.

In the tapestry of Fats Domino’s career, “Swanee River Hop” stands out not for its chart position but for its raw, rollicking piano energy. Unlike his vocal hits like “Ain’t That a Shame” or “Blueberry Hill,” this track puts his ivory mastery front and center. The song charts his virtuosity rather than a climb of the Billboard rankings, but it became a staple in his repertoire, especially in small New Orleans venues. According to accounts, Domino’s version of this piece—based on Albert Ammons’s “Swanee River Boogie”—was frequently played in tiny Ninth Ward nightspots, where the rhythmic joyfulness of boogie-woogie merged seamlessly with his signature R&B groove.

Recorded as early as April 1953 during sessions at Radio Recorders in Hollywood, “Swanee River Hop” was later collected on his second studio LP, Rock and Rollin’, which was released in 1956. While Rock and Rollin’ was not his debut—his first LP was Rock and Rollin’ with Fats Domino in March 1956 —this follow-up album provided a canvas for Domino’s more playful, instrumentally driven pieces, with critics praising “Swanee River Hop” as a genuine virtuoso performance.

At its heart, “Swanee River Hop” is a joyful conversation with musical ancestry. Its lineage stretches back to Stephen Foster’s 1851 composition “Old Folks at Home (Way Down Upon the Swanee River),” with Domino drawing inspiration not directly from Foster’s minstrel-era song, but rather from Albert Ammons’ boogie-woogie interpretation, “Swanee River Boogie.” Through this reimagining, Domino connects with a tradition—a lineage of piano players who transformed a 19th-century melody into a vehicle for swing, joy, and improvisational freedom.

Domino’s version isn’t just a respectful nod; it’s a full-throttle reclamation. His left hand thunders with the steady, driving pulse of boogie-woogie, while his right hand races across the keys in sparkling runs and playful, cascading embellishments. There’s no vocal melody to guide the listener—only the piano, rhythm section, and mood. Yet somehow, it communicates more than words ever could: a celebration of roots, of place, and of the deep wells of musical instinct that nourished New Orleans’ R&B tradition.

In live settings, “Swanee River Hop” became emblematic of Domino’s early club performances. According to accounts, it featured in his sets at The Hideaway, a humble bar in the Ninth Ward, where he and Dave Bartholomew forged their working partnership. The piece invited both listeners and fellow musicians into a shared space of raw improvisation and unfiltered joy—Domino didn’t just perform it; he seemed to inhabit it.

Importantly, the song reflects Domino’s dual identity as a rooted, soulful R&B singer and a pianist steeped in the boogie-woogie and jazz traditions of his influences. While his vocal hits made him a star, pieces like this one underscore his foundation: a deep, unshakeable bond with the piano. Bruce Eder, writing about Rock and Rollin’, described “Swanee River Hop” as “a genuine virtuoso performance at the ivories.”

Over time, the tune’s cultural legacy expanded. It connects not only to boogie-woogie piano but also to a broader tapestry of New Orleans musical history. Its spirit echoes in later live renditions—Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Ray Charles once performed a variant called “Swanee River Rock.” Through such moments, the piece transcended its original recorded form and lived on as a kind of anthem—a testament to how deep musical traditions can be reshaped, revived, and reimagined without losing their soul.

In reflecting on “Swanee River Hop,” one feels the beautiful tension between tradition and innovation. It is by no means a hit single with high chart glory, but precisely because of that, it reveals a more intimate facet of Fats Domino: the pianist who doesn’t just sing; he converses, celebrates, and reveres his musical forebears, all while forging his own path. The result is a moment of pure, unadulterated piano joy—a snapshot of a master in full command, dancing across the keys in homage to the river of music from which he drew.