A Dream of Wide‑Open Land and a Lone Cowboy Heart

“I’m Gonna Be a Cowboy” is a wistful Western reverie spun by Marty Robbins, recorded in the mid-1960s and appearing on his 1966 album The Drifter. While not one of his chart-topping singles, this song occupies a cherished place in Robbins’s canon — a quietly hopeful anthem of longing, identity, and the romantic myth of the frontier.

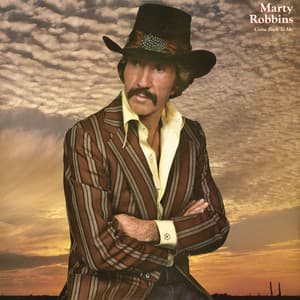

Robbins, already renowned for his cinematic ballads like El Paso and Big Iron, infused this piece with his trademark poetic clarity. Written by Robbins himself, I’m Gonna Be a Cowboy first appeared in his catalog in 1966.While it may not have cracked the country charts as a single, the song later gained renewed exposure on compilation albums like The Essential Marty Robbins (1951–1982).

At its heart, I’m Gonna Be a Cowboy is a portrait of aspiration — not just to ride and rope, but to live a kind of mythic life under wide skies. Robbins’s lyrics evoke a ten-gallon Stetson, cattle grazing across a “great big piece of land,” a moonlit Arizona ranch, and the longing for a life measured in sunsets, silver-trimmed saddles, the touch of velvet felt in a saddle seat. There’s nothing sinister here — the cowboyhood he dreams of is more ideal than outlaw, more timeless than transactional.

Musically, the structure is simple yet effective: Robbins leans into a gentle chord progression (Eb, F, Bb, etc.), creating a steady, rolling rhythm that feels like a slow ride across the prairie. His warm baritone voices the yearning, but the arrangement stays understated — he doesn’t need thunderous guitars or dramatic flourishes. The restraint gives the song a meditative quality, as though Robbins is speaking into a starlit sky instead of singing at a crowded dance hall.

One striking thing about this song is how it encapsulates Robbins’s dual identity as both a Western romantic and a grounded realist. He wasn’t just fantasizing — he was channeling a deeply held ideal rooted in American Western mythology. In Robbins’s own life, as historian Diane Diekman notes, he often gravitated toward Western themes: his albums brimmed with gunfighter ballads, desert imagery, and stories of wandering souls. In The Drifter, critics have called his work “one of the purest cowboy albums Robbins ever made.”

Yet I’m Gonna Be a Cowboy isn’t a conflict song. There’s no vengeance or bloodshed. Instead, it’s deeply personal — it’s a manifesto of self-definition. Rather than chasing lawlessness, the narrator seeks belonging; rather than glorifying gunfights, he romanticizes peace under the stars. Robbins was a master of emotional subtlety: he doesn’t shout his dreams, he whispers them. You hear a man who’s not demanding anything from the world, just declaring who he wants to become.

In the larger context of Robbins’s career, this song offers a gentle counterpoint to his more narrative-driven western epics. While El Paso dramatizes life and death, I’m Gonna Be a Cowboy meditates on longing. It’s a quieter kind of legacy — the dreamer’s dream rather than the gunfighter’s showdown.

For longtime listeners and newcomers alike, I’m Gonna Be a Cowboy stands as a testament to Robbins’s poetic heart. It’s a reminder that some dreams endure not because they’re inevitable, but because they’re deeply true.