A farewell sung across the plains – lonely, timeless, and still echoing in the heart of the valley.

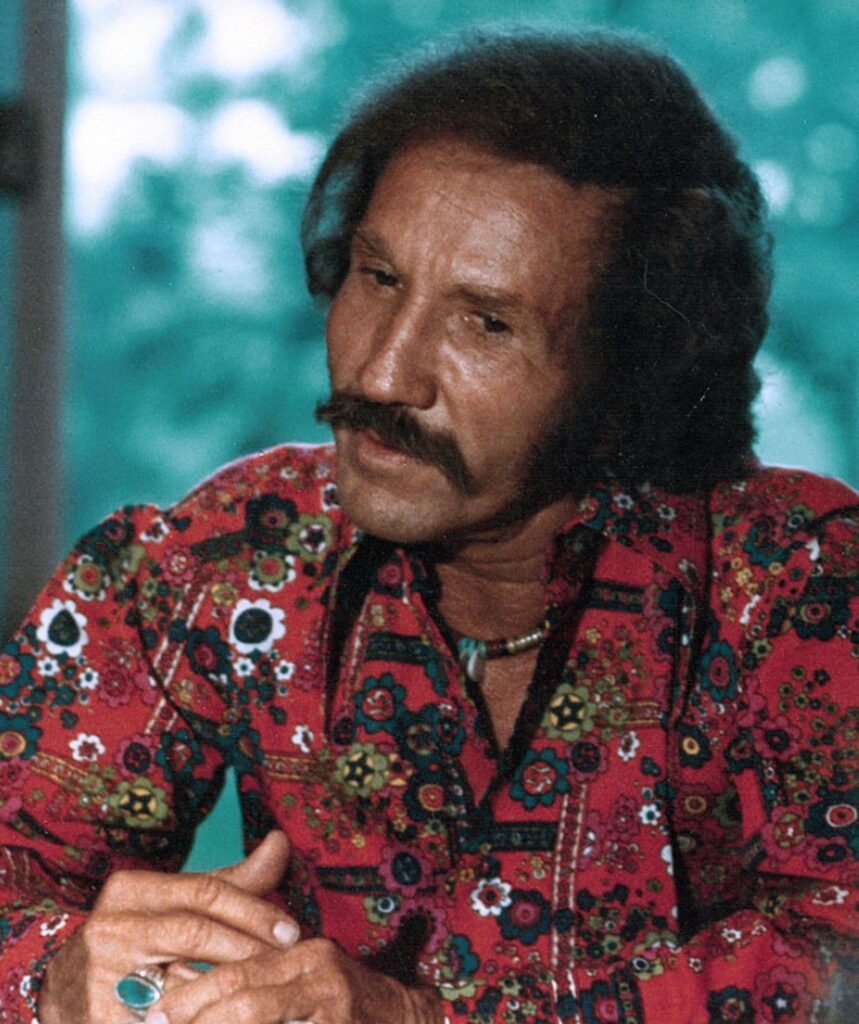

When Red River Valley appears in the catalogue of Marty Robbins, it carries with it the gentle weight of tradition and the subtle artistry of a singer who understood the emotional geography of the Western song. Robbins recorded this traditional standard, first documented in the early 20th century, on May 25, 1960; it was released as part of his compilation album More Greatest Hits in April 1961. While precise chart performance figures for this version are scarce, it remains a poignant moment in Robbins’ extensive body of work—a rare instance of him embracing the folk ballad form rather than one of his original Western narratives or radio-friendly country singles.

In the hushed opening of Robbins’ rendition, one senses more than just a singer performing a well-worn song; one senses a man pausing at the river’s edge, looking back at what is left behind and ahead at what may become. The lyrics trace the departure of a loved one: “From this valley they say you are leaving, we shall miss your bright eyes and sweet smile…” In Robbins’ voice, that departure is not merely physical—it is thematic: the leaving of innocence, the quiet surrender to change, the unspoken longing for something lost or unattainable. The sparse instrumentation—his soft, steady baritone supported by an acoustic guitar and subtle backdrop—highlights the song’s deep roots in the folk-tradition, allowing Robbins’ interpretive skill to bring new light to an old lament.

It is important to note that “Red River Valley” is not original to Robbins; its authorship remains anonymous, its first recordings dating back to the 1920s. In choosing to record it, Robbins placed himself within a lineage of Western balladeers and folk singers, yet he did so with the polish of a country star who knew the value of authenticity. The “valley” of the song is both literal and metaphorical—a place of departure, memory, and longing. Through Robbins’ interpretation, the valley becomes a landscape of the heart: where the sun sets on one’s youth, and the river carries away the echoes of a familiar voice.

Musically, this recording sits apart from Robbins’ more cinematic Western narratives like El Paso or his pop-inflected honky-tonk hits. Instead it is quiet, reflective. The pacing is measured; the emotional tension lies not in dramatic gunfights or cowboy exploits but in silence—what is said in parting, what remains unsaid when someone walks away. Robbins’ performance invites the listener to imagine the scene: the open plain, the fading daylight, the figure at the bank looking back. In doing so, he transforms a song that had been sung by countless others into one that bears his unmistakable stamp of sincerity.

In terms of legacy, Robbins’ version of “Red River Valley” serves as a reminder of the versatility of his artistry. Even when he steps away from the spotlight of chart-topping singles and dramatic Western ballads, he demonstrates his ability to inhabit the quiet spaces of American music—the places where hearts ache, memories linger, and time seems to stretch out like the plains themselves. For the mature listener, this version is not a footnote but a moment of stillness in the catalog of a man who was never afraid to wander between genres and styles.

In sum, Robbins’ “Red River Valley” offers a gentle but profound meditation on departure, nostalgia, and the bittersweet pulse of change. It is less about the blaze of fame or the thrum of the rodeo and more about the soft, enduring echo of a valley song carried on the wind—one that Robbins, in his inimitable voice, made feel both personal and eternal.