A quiet hymn of innocence and sorrow carried across centuries into the gentle hands of a modern voice

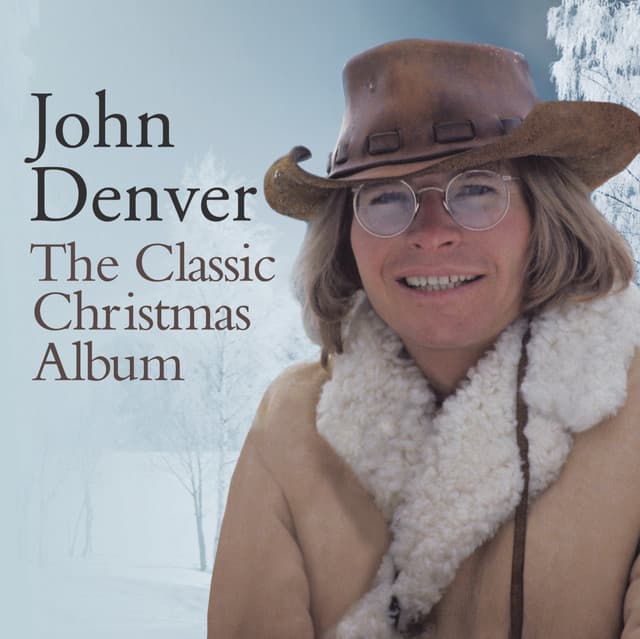

When John Denver recorded Coventry Carol for his 1990 holiday album Christmas Like a Lullaby, he brought one of the oldest surviving English carols into a contemporary setting without disturbing the delicate emotional fabric that has defined the piece since the sixteenth century. Although the track was never positioned for chart success, its inclusion on a major studio album by one of America’s most recognizable voices introduced countless listeners to a centuries old lament that lies far from the familiar warmth usually associated with seasonal music. Denver approached the song not as a commercial entry but as a preservation of sacred emotional memory, allowing his album to serve as a vessel for a timeless narrative of compassion and grief.

Coventry Carol descends from the traditional Mystery Plays performed in Coventry, England, and its origin lies in the dramatization of the Massacre of the Innocents. The carol was written as a cradle song sung by mothers who fear the loss of their children in a time shadowed by violence. This historical foundation gives the piece a gravity that surpasses its liturgical context. Even without explicit storytelling, the very melody carries the weight of a collective sorrow that has echoed through generations.

Denver’s interpretation rests on restraint, a musical humility that respects the age of the composition. He allows the melody’s minor tonality to guide the emotional arc. His voice neither challenges nor embellishes the original framework. Instead, he becomes a narrator suspended between past and present, offering listeners a direct connection to a song shaped by centuries of performance. The arrangement is kept spare, giving the lingering intervals space to resonate with the listener. This quietness becomes a form of reverence, honoring the mothers at the heart of the carol.

Lyrically, the song is a lullaby built on contradiction. It soothes by acknowledging grief. It comforts by naming fear. Denver’s delivery underscores this paradox. His gentle phrasing emphasizes the way the text balances tenderness with tragedy, creating a musical space where sorrow becomes a shared human experience rather than an isolated historical moment. In a cultural environment where Christmas music often leans toward celebration, Coventry Carol stands as a meditative counterpoint that invites listeners to reflect on vulnerability, loss, and the fragile sanctity of childhood.

Through this interpretation, Denver extends the legacy of the carol. He does not modernize it. He illuminates it. The song becomes not merely a historical artifact but a living emotional bridge, a reminder that even across centuries, human grief and human tenderness remain intertwined.