Confession where sorrow outlasts the bottle and memory proves the stronger poison

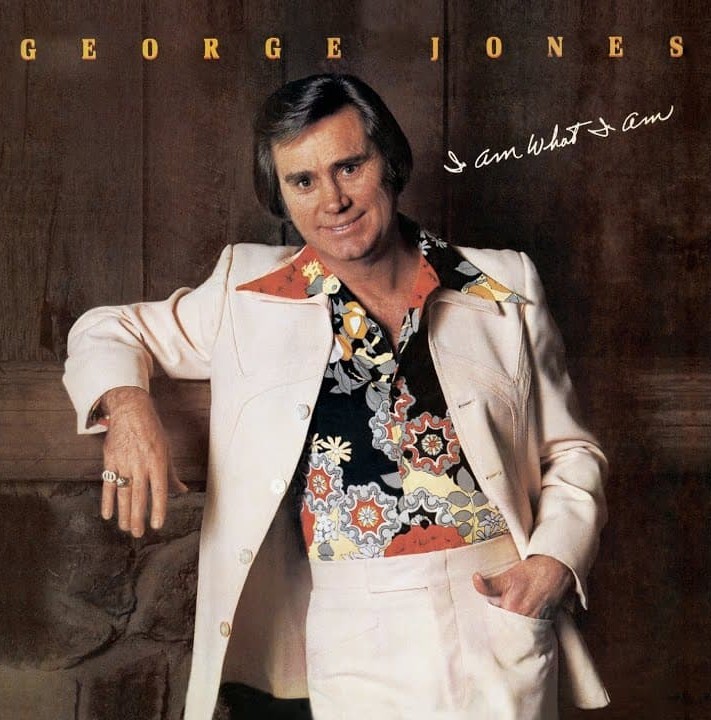

Released in 1973, If Drinkin’ Don’t Kill Me (Her Memory Will) climbed to Number Five on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart, standing as one of the most revealing performances of George Jones’ early seventies peak and closely tied to the stark emotional world of the album I Am What I Am. At a time when Jones was already cemented as country music’s most unguarded voice, the song arrived not as a novelty of heartbreak but as a document of lived experience, delivered without ornament or mercy.

What distinguishes If Drinkin’ Don’t Kill Me (Her Memory Will) from the many drinking songs that populate country music is its refusal to romanticize escape. Alcohol is not framed as rebellion, camaraderie, or even relief. It is presented as a last and failing defense against memory itself. The title alone functions as a grim thesis. Drinking is no longer the danger. Remembering is. This inversion gives the song its lasting power, because it strips away the genre’s usual coping mechanisms and leaves only exposure.

Jones’ vocal performance is central to this effect. He sings with a weary steadiness that suggests the argument has already been lost. There is no slur, no dramatized collapse. Instead, the phrasing is controlled, almost restrained, as if the narrator understands the futility of excess but continues anyway out of habit rather than hope. This restraint is what makes the song devastating. The listener hears not a man spiraling, but one who has already settled into the aftermath.

Lyrically, the song acknowledges a truth that country music often circles but rarely confronts directly. Pain does not diminish with repetition. Memory sharpens in silence. Each line reinforces the idea that emotional wounds do not fade simply because time passes or substances intervene. The drinking becomes procedural, a ritual performed nightly, while the memory remains vivid and untouchable. This is not heartbreak in its first bloom, but in its long middle stretch, where endurance replaces drama.

Musically, the arrangement supports this emotional stasis. The instrumentation stays grounded and unintrusive, allowing Jones’ voice to carry the narrative weight. Nothing rises to rescue the singer. Nothing collapses beneath him either. The song exists in equilibrium, mirroring the narrator’s suspended state between survival and surrender.

Culturally, If Drinkin’ Don’t Kill Me (Her Memory Will) stands as one of the clearest windows into why George Jones became synonymous with emotional truth in country music. The song does not rely on biography, yet it resonates more deeply because of the public knowledge of Jones’ struggles. Still, its strength lies in universality rather than confession. Anyone who has discovered that distraction fails against remembrance will recognize themselves here.

Decades later, the song endures because it tells an uncomfortable truth with dignity. It suggests that some losses do not heal, only integrate. The pain does not disappear. It learns how to sit quietly. In that honesty, George Jones offers something rarer than comfort. He offers recognition.