A jubilant confession where earthly love is lifted into something bordering on the sacred

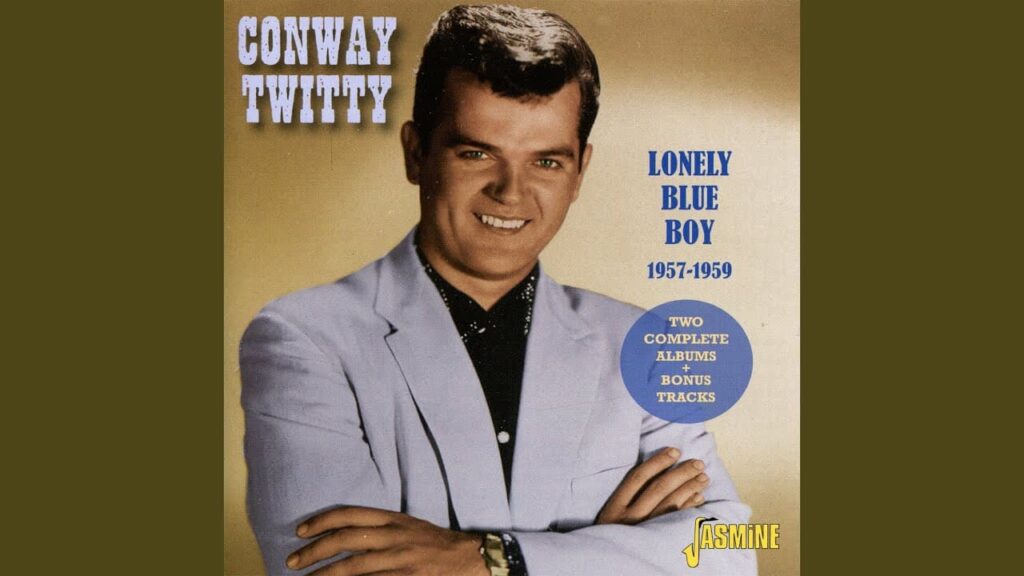

When Conway Twitty recorded Hallelujah, I Love Her So, he was still navigating the borderlands between early rock and roll and the country identity that would later define him. The song never stood as a chart defining moment in his catalog, nor did it anchor a flagship album release. Instead, it emerged during his formative recording years, issued as part of his early Decca era output, when commercial certainty mattered less than feel, phrasing, and raw conviction. Yet even without headline chart numbers, this performance remains a revealing artifact, capturing an artist in the act of learning how to translate joy into sound.

Originally written and made famous by Ray Charles, the song is built on a simple but potent premise. Gratitude becomes romance. Love becomes testimony. In Twitty’s hands, the familiar structure takes on a different gravity. Where Charles framed the song with gospel inflections and rhythmic swing, Twitty approached it from a more restrained, almost reverent angle. His voice does not shout hallelujah. It leans into it. That choice matters. It reframes the song not as exuberant celebration alone, but as something closer to lived thankfulness.

Lyrically, Hallelujah, I Love Her So is deceptively modest. There is no grand tragedy, no tortured longing. The narrator wakes up fed, cared for, and emotionally anchored. In the canon of American popular music, that perspective is rare. Most love songs chase desire or mourn its loss. This one pauses to acknowledge stability. Twitty understood that power. His delivery lingers on lines about everyday devotion, turning domestic detail into quiet revelation. The song becomes less about romance as spectacle and more about romance as shelter.

Musically, the arrangement stays uncluttered, allowing rhythm and vocal phrasing to do the heavy lifting. Twitty’s background in early rockabilly surfaces in the subtle drive of the performance, but he resists excess. There is discipline here. Each phrase lands cleanly, without ornamentation that might distract from the sentiment. That restraint would later become one of his greatest strengths as a country vocalist. In retrospect, this recording feels like a rehearsal for emotional precision.

Culturally, Hallelujah, I Love Her So occupies an important crossroads. It sits at the intersection of gospel, rhythm and blues, and early rock, interpreted by an artist who would soon pivot toward Nashville and redefine himself entirely. For listeners who know Conway Twitty only through his country hits, this performance offers a valuable recalibration. It reminds us that before the polished ballads and chart topping duets, there was a singer learning how to honor joy without irony.

In the end, Twitty’s rendition does not attempt to surpass the song’s original legacy. It does something quieter and arguably more enduring. It bears witness. It treats love not as drama, but as blessing. And in doing so, it preserves a moment when a young artist recognized that sometimes the most radical thing a song can say is thank you.