A jubilant declaration of rural pride where simple labor, family, and community become a complete philosophy of joy.

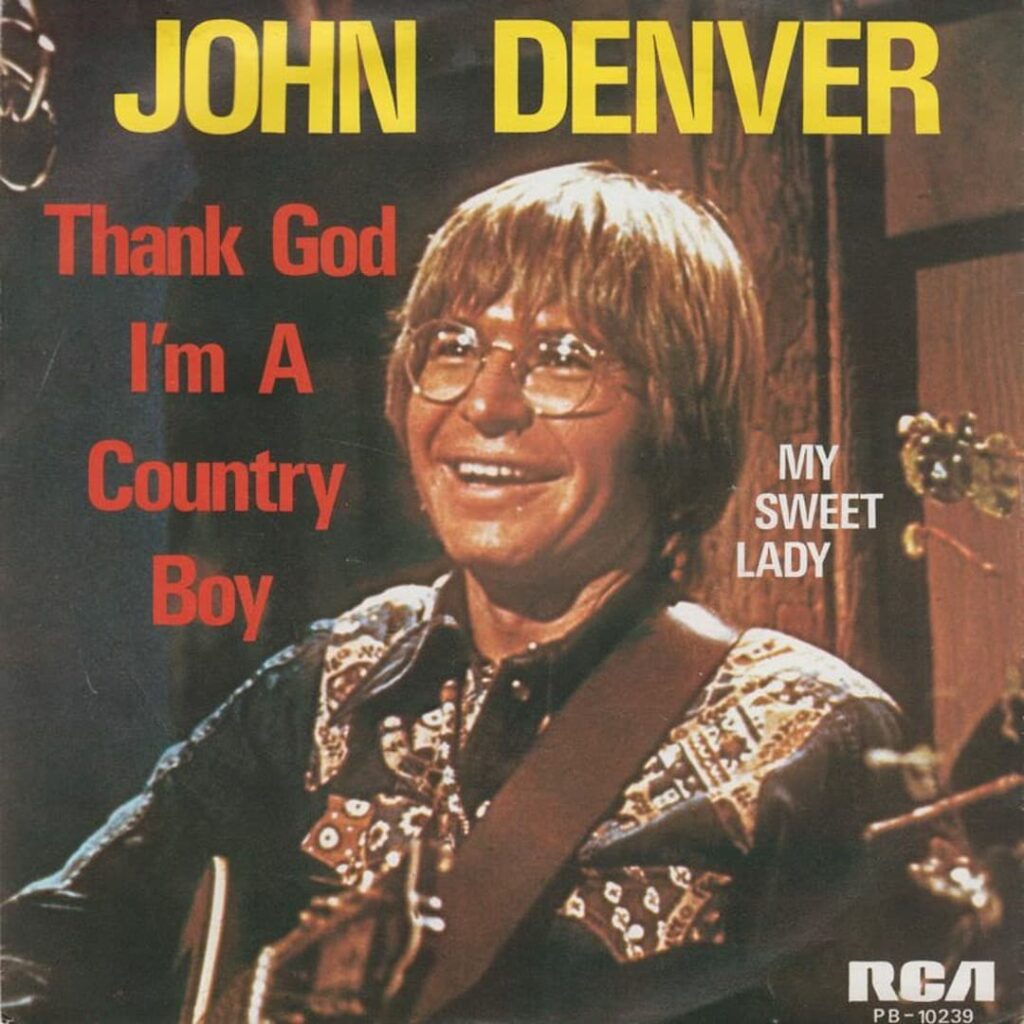

When John Denver released “Thank God I’m a Country Boy” on his 1974 album Back Home Again, few could have predicted that this brisk, fiddle driven celebration would become one of the most enduring expressions of American pastoral identity in popular music. Issued as a single in its now famous live version recorded at the Universal Amphitheatre, the song rose to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 in early 1975 and simultaneously topped the Hot Country Singles chart, a rare crossover achievement that reflected Denver’s singular position at the intersection of folk sincerity, country tradition, and mainstream pop appeal.

At its surface, “Thank God I’m a Country Boy” appears disarmingly simple. Its lyrics unfold as a catalog of rural pleasures: waking with the sun, working the land, sharing meals, playing music, and returning home to a devoted wife. Yet this simplicity is precisely the song’s strength. Written by Denver with long time collaborator Bill Danoff, the composition functions less as a narrative and more as a manifesto. It is not about a single day or a single man, but about a worldview rooted in gratitude and continuity. The repeated refrain is not merely celebratory; it is declarative, almost devotional, framing country life as a moral and spiritual anchor in a rapidly modernizing America.

Musically, the song leans heavily on traditional Appalachian textures. The prominent fiddle line, the driving acoustic rhythm, and the communal call and response structure evoke front porch gatherings rather than recording studios. Denver’s vocal delivery is notably relaxed and conversational, emphasizing warmth over virtuosity. In concert, the song became a participatory ritual, with audiences clapping, shouting, and briefly dissolving the boundary between performer and listener. That live energy is what propelled the single to the top of the charts, capturing not just a performance but a shared emotional experience.

Culturally, the song arrived at a moment of national fatigue. The mid 1970s in the United States were marked by political disillusionment, economic anxiety, and the aftershocks of social upheaval. Against that backdrop, “Thank God I’m a Country Boy” offered neither protest nor escape, but reassurance. It suggested that fulfillment could still be found in work done with one’s hands, in family bonds, and in the rhythms of the natural world. Importantly, Denver’s country boy is not defined by exclusion or nostalgia for a lost past. Instead, he is defined by presence, by gratitude for what is already enough.

Over time, the song has been both celebrated and caricatured, sometimes dismissed as overly wholesome or idealized. Yet its endurance argues otherwise. More than five decades later, it remains a fixture at sporting events, festivals, and radio stations, continuing to resonate with listeners far removed from farms or fields. Its power lies not in realism but in aspiration. John Denver did not merely write a song about rural life. He preserved a feeling, a sense that joy does not need complexity, only attention. In the grooves of Back Home Again, “Thank God I’m a Country Boy” stands as a timeless reminder that gratitude, once set to music, can become a form of cultural memory.