The Big O’s Bitter Dirge: A Heartbreak That Echoed War’s Cruelty

Ah, Roy Orbison. The name itself conjures up that singular blend of velvet sorrow and operatic drama that defined a whole era of pop music. Many remember him for the high-octane heartbreak of “Oh, Pretty Woman” or the sweeping agony of “Crying,” but today, let’s step off the brightly lit stage and into the shadowed corners of his repertoire for a moment of quiet, devastating reflection. We’re turning back to 1966 for the solemn, often-overlooked gem, “There Won’t Be Many Coming Home.”

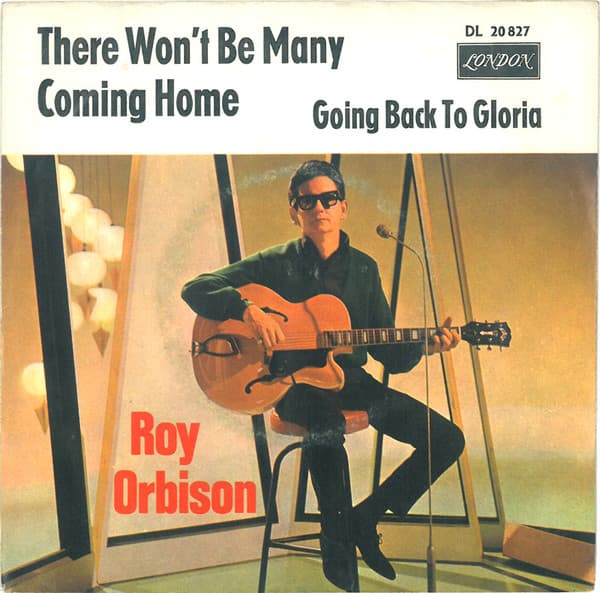

The song, a co-write with his frequent collaborator Bill Dees, was first released in the U.K. as a single in late 1966. For those of us who kept a close eye on the Official Charts back then, the single performed admirably, settling at a peak position of Number 12 and spending a respectable nine weeks among the elite. This was a welcome showing, especially as Orbison was transitioning his career and his sound onto the MGM Records label.

However, the deeper story behind this track lies not just in charts, but in celluloid. The song became a key, though somewhat orphaned, part of the soundtrack for Orbison’s foray into acting: the 1967 musical-comedy Western film, The Fastest Guitar Alive. While the movie itself was a critical and commercial flop—a quirky tale of a Confederate spy with a gun-shooting guitar—the album, also titled The Fastest Guitar Alive, proved to be a unique entry in the Orbison catalog, being the only one composed entirely of Orbison and Dees originals. Curiously, despite being featured on the soundtrack, “There Won’t Be Many Coming Home” was deemed too melancholy to actually make it into the final cut of the rather campy movie. The irony is as thick as the sorrow in Roy’s voice: a song about ultimate, tragic loss shelved for being too real.

Its power lies in its unadorned, chillingly literal meaning. Far from the metaphor of a broken romance, the lyrics speak plainly of the brutal arithmetic of war. “Listen all you people / Try and understand / You may be a soldier / Woman, child or man / But there won’t be many coming home.” It is a stark anti-war ballad, a slow, mournful march accompanied by those signature, swirling strings and ghostly backing vocals that make the whole thing feel like a lament heard from beyond the veil. The heart of the song is in the diminishing numbers—”maybe ten out of twenty,” then “maybe five out of twenty,” until the chilling final reduction: “There may not be any.”

For those of us who lived through the shadow of one conflict or another, or who simply remember the pall of an evening news bulletin, this song holds an almost unbearable poignancy. It doesn’t glorify the fighting; it focuses on the hollow triumph, the ‘glory’ that is “all gone,” leaving the old folks with hearts “choked with pride” that turns to choking grief. It’s an epitaph for the fallen, a stark reminder that every uniform is someone’s child, and every empty chair is a permanent wound. The song achieved a remarkable second life in 2015 when director Quentin Tarantino used it to close his Western, The Hateful Eight, a context that perfectly underscored the film’s own themes of senseless, inevitable bloodshed. It proved that a true classic, however quiet, will eventually find its rightful, resonant audience. This track is a masterclass in controlled, yet utterly devastating, emotion—a sound you can practically taste, like dust and tears.