A quiet voice in the dark reveals the painful distance between two people who can no longer reach each other

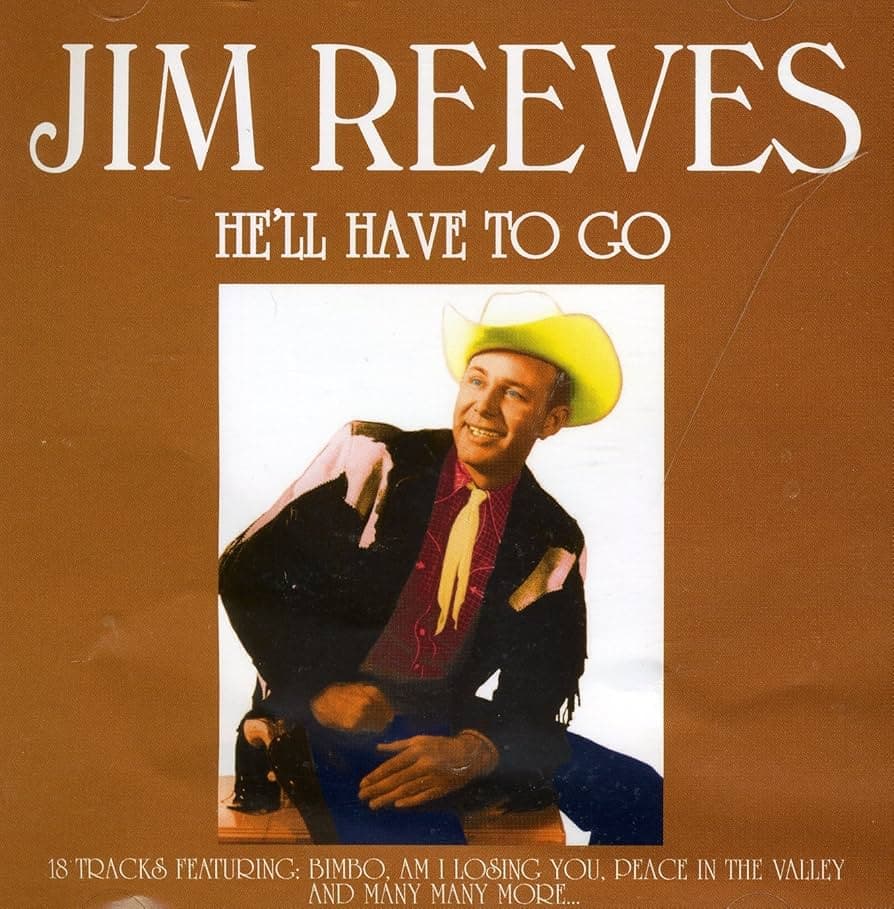

When Jim Reeves released He’ll Have to Go in late 1959, the single quickly became a defining moment in his career. It rose to the top of the country charts and crossed into the mainstream, reaching the upper ranks of the Billboard Hot 100 in early 1960. The recording later appeared on the 1960 RCA album He’ll Have to Go, where its smooth production and intimate vocal style helped cement Reeves as a leading figure in the Nashville Sound. From its first note, the song signaled a shift in the emotional vocabulary of country music, introducing a level of whispered vulnerability that felt startling in its restraint.

The story behind He’ll Have to Go is one rooted in simplicity, clarity, and emotional directness. Written by Joe Allison and Audrey Allison, the composition relies on a fragment of a phone call to illuminate an entire relationship. Reeves approached the song with a characteristic calm that belied the turmoil within its lyrics. His baritone glided over the arrangement with a quiet authority that turned a personal plea into something universal. Every phrase feels measured, almost hushed, as if he is leaning in toward the listener, asking them to feel the tension of a conversation that is teetering on the edge of farewell.

The meaning of the song rests in its duality. On the surface, it is a straightforward request: a man asks his lover to tell another presence in the room to leave, so that he can speak to her honestly. Beneath that, however, lies a profound discomfort. The intrusion of background noise, the uncertainty in her voice, and the need to articulate such a plea all point to a relationship that has already begun to fracture. Reeves uses the geometry of distance to build the drama. He is far away, reliant on a telephone. She is close to someone else, physically and possibly emotionally. The line between them is literal and symbolic, a wire carrying words that may no longer be enough to hold them together.

Musically, He’ll Have to Go is an exemplar of the Nashville Sound’s polished minimalism. The gentle rhythm section and soft background vocals create space around Reeves, allowing the intimacy of his delivery to dominate the atmosphere. Nothing competes with the emotional weight of the lyric. Instead, the arrangement mirrors the song’s narrative structure. Each instrumental line feels like another room being emptied, clearing a path toward the raw truth at the center.

The cultural legacy of He’ll Have to Go rests on its ability to say something quietly but irrevocably. It captures the moment when love has not yet ended, but the recognition of its fragility can no longer be ignored. Reeves transformed a simple telephone exchange into one of the most enduring meditations on longing in twentieth century popular music.