A HEART HUNGRY TO FORGET

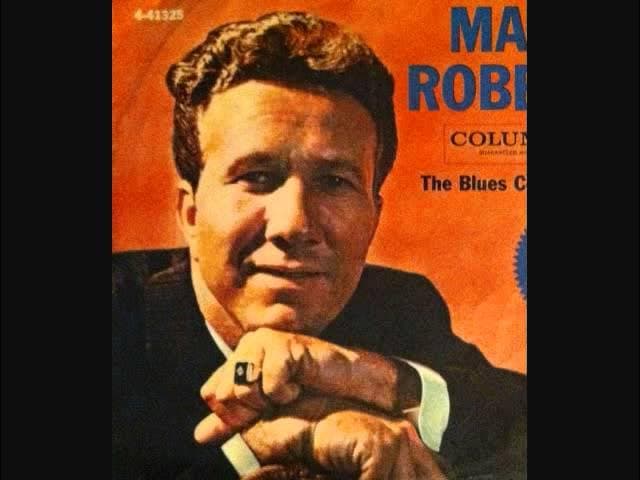

When the needle drops on Change That Dial, the ache of regret and the sharp sting of lost love wash over everything. The song — from Marty Robbins’ 1964 album R.F.D. — may not have conquered the pop charts, yet it belongs to the deeper emotional undercurrent of Robbins’ work at a time when he was quietly steering away from epic “gunfighter” sagas and toward the small, aching moments of the heart. R.F.D. peaked at No. 4 on the Billboard country album chart and stayed on the chart for 28 weeks, marking a period of steady acclaim for Robbins.

In the world of “cowboy ballads” and sweeping western landscapes, “Change That Dial” stands as a whisper — the sort of intimate, regret‑heavy confession that reveals pain without spectacle. The song opens with a plea: “Change the dial, turn off that song. It reminds me of something I’ve done, something so wrong.” In those handful of lines, Robbins isn’t just addressing a radio; he is addressing memory itself, that cruel jukebox of what was once love and now is loss.

The narrator recounts a love that was once “real, true”: meaningful in its fidelity and promise. But he broke that promise. He strayed. She discovered the betrayal and vanished. The “same old song” they once sang together — probably a tender ballad marking better days — becomes unbearable now. Hearing it is a knife twisting deeper, forcing him to confront the betrayal over and over again. Lyrics do not dramatize jealousy or rage; they channel simmering shame and grief. The repetition of “change the dial” reshapes the radio knob into a metaphorical lever, urging the listener to erase the soundtrack of guilt and sorrow.

Musically the song reflects this stripped‑down confession. The arrangement is modest — acoustic guitar, soft supporting instrumentation — nothing grand nor theatrical. It recalls the simplest sessions of early 1960s country: raw voice, spare backing, room for silence in between the chords. This sonic choice frames the vulnerability of the narrator, makes room for the listener to feel the emptiness he now carries. In a sense, “Change That Dial” offers an emotional austerity much like the landscapes of the western ballads Robbins is better known for — but instead of wide deserts and lonely trails, its emptiness is internal, spiritual.

In the arc of Robbins’ career, “Change That Dial” marks a quiet but meaningful turn away from the mythic West toward emotional introspection. On R.F.D. he is not the wandering gunslinger or the tragic outlaw; here he is a man stranded by memory, trying to silence the song that betrayed him — not with confrontation, but with quiet contrition and longing.

For a listener willing to lean in close, the song becomes a late‑night confession, a moment when regret is allowed to breathe and music becomes a ledger for pain. “Change That Dial” may never have been a blockbuster hit, but it stands as a testament to the power of subtlety: a refusal to dramatisize heartbreak, choosing instead to capture it in the low hum of guilt, the soft strum of a guitar, the sound of a radio knob turned slowly away.

In that motion, there is loss — and something like redemption.