The Blood-Stained Desert of Retribution

A stark, somber tale of generational revenge and the crushing, nihilistic cycle of violence in the Old West.

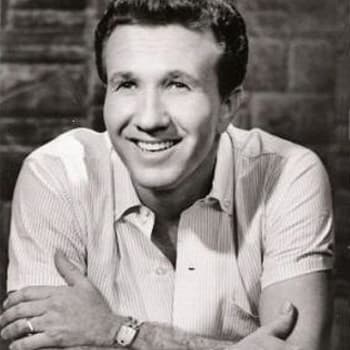

In the vast, resonant catalog of Western ballads immortalized by the incomparable Marty Robbins, few songs capture the grim, relentless spirit of frontier justice—or perhaps, frontier tragedy—quite like “Five Brothers.” Released on a Columbia single in 1960, the track appeared as the B-side to “Is There Any Love for Me,” and was later included on his seminal album, More Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs, a follow-up to the iconic 1959 collection. Though it did not reach the staggering heights of “El Paso” or “Big Iron,” “Five Brothers” carved out its own place in the country and pop landscape, peaking at a respectable No. 26 on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart, and making minor showings on the Pop charts, reaching No. 74 on Billboard‘s Hot 100 and No. 76 on Music Vendor. Its presence on the charts, even outside the Top 10, signaled the enduring appetite for Robbins‘ masterful, narrative-driven Western storytelling.

The story, penned by Tompall Glaser (of the famed Glaser Brothers, who often provided backing vocals for Robbins), is a raw, heart-wrenching chronicle of five sons—three of them still in their teens—who set out on a desperate, burning quest for vengeance. Their father, their “pa,” was murdered by a gambler in New Orleans. The opening lines set the desperate tone: “Five brothers who left Arkansas / Set out to find the gambler who murdered their pa.” This is not a tale of a clean duel or a hero upholding the law; this is a slow, agonizing chase fueled by youthful fury and a profound, shared grief.

As the narrative unfolds, the listener is taken on a desolate journey that echoes the unforgiving nature of the Wild West mythos. The brothers’ trail leads them westward, through the harsh lands beyond Houston, where “the desert promised death.” The very landscape becomes a character, mirroring the emotional void and moral desolation of the chase. These boys are driven by an elemental need for retribution, a primal eye-for-an-eye justice that ultimately blinds them to their own peril. The meaning is devastatingly clear: the pursuit of vengeance, particularly one so intensely focused and all-consuming, leads only to self-destruction.

Marty Robbins‘ delivery, with that smooth, evocative baritone, elevates the song from a simple narrative to a profound, tragic folk epic. He doesn’t sing the violence with bravado; he narrates the relentless journey with a sense of inevitability and a mournful, almost historical detachment, making the ending all the more poignant. When they finally find the killer by a water hole and “five rifles rang out through the night,” the sense of triumph is fleeting, instantly overshadowed by a dark twist: “The desert is their keeper now for this is what they’d said / That poison lived within the hole, now six of them are dead.”

The shocking conclusion—that the killer and the five avenging brothers all drink poisoned water and die together—is what cements “Five Brothers” as a profound statement on the futility of revenge. It’s a twist of cruel fate that strips away any satisfaction from their successful hunt. The six men, united by a fatal act and a fatal retribution, lay side-by-side in the desert sand. For an older generation who grew up with the simplified morality of classic Western films, this song offers a far more complex, nihilistic vision of the frontier. It’s a reflection on the deadly cost of carrying a grudge and a stark reminder that in the harsh reality of the Old West, violence begat only more violence, leaving no one truly victorious, only “six of them… dead” in the unforgiving earth. It is this powerful, sobering reflection that allows the song to linger in the memory, a haunting masterpiece among Robbins‘ legendary trail songs.