A Blazing Ballad of Man, Horse, and the Terrifying Majesty of the Old West

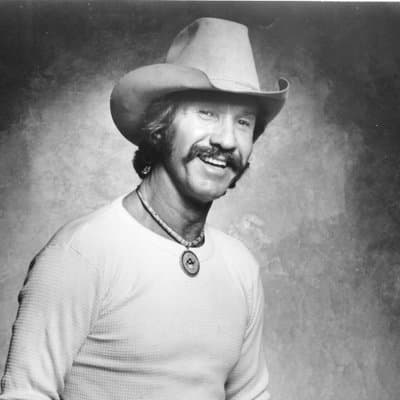

For those of us who came of age with the dust and drama of the Western genre filling our airwaves and imaginations, the music of Marty Robbins holds a special, sun-drenched place. His 1959 masterpiece, Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs, redefined the Western narrative in music, and when he returned a year later with its splendid sequel, More Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs, we were eager for more tales of the dusty trail. Released in July 1960, the album featured a lesser-known gem that nevertheless captured the breathtaking danger of the frontier: “Prairie Fire.”

While many of the tracks on the Robbins albums—like “El Paso” and “Big Iron”—became massive, cross-over hits, achieving high chart positions on both country and pop charts, “Prairie Fire” did not achieve the same single success. It was, instead, an essential component of the album experience, a deep cut that showcased Robbins’s gift for vivid storytelling and mood-setting. The album itself, More Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs, continued the legacy of the first, a vital part of the Western music revival, but the track “Prairie Fire” was not released as a charting single. This fact only seems to make it more cherished by those who own the album—a true diamond found in the musical rough, unburdened by the relentless demands of the radio dial.

“Prairie Fire” is a quintessential trail song, a tense, immediate, and utterly captivating tale of survival against nature’s fury. Written by the underrated songwriter Joe Babcock, the song is a first-person account of a cowboy desperately racing to outrun a massive, uncontrolled firestorm sweeping across the plains.

The meaning of the song is straightforward yet profound: it is an ode to the terrifying power of the wild and the desperate courage it takes for a man to face it. It perfectly captures that overwhelming, helpless feeling when all of man’s creations—his fences, his structures, his ambitions—are rendered meaningless by a force of nature. The cowboy, with his life hinging on the speed and stamina of his horse, is reduced to a primal state. The lyrics paint a scorching landscape, focusing on the sounds and sights of the encroaching flames, emphasizing the relentless, consuming pace of the fire. The narrator’s final, desperate plea to his faithful horse, “Run, run, run!” is a moment that sends a genuine chill down the spine, connecting us instantly to the life-or-death struggle.

This immediacy is what defined the appeal of these “Gunfighter Ballads.” Marty Robbins didn’t just sing; he inhabited these characters, his voice a masterclass in conveying raw anxiety and determination. When he sings, you can almost smell the smoke, feel the heat on your face, and taste the grit kicked up by the frantic gallop.

Listening to “Prairie Fire” today is more than just appreciating a great song; it’s a nostalgic trip back to a time when storytelling in music was an art form unto itself. Robbins’s rich baritone, coupled with the atmospheric acoustic guitar work, conjures up the romanticized vision of the Old West that was so potent in our youth. It’s a vision not just of heroes and villains, but of man against the landscape—a powerful, rugged honesty that modern music often seems to miss.

For older readers, this song taps into a deeper well of memory. It recalls the golden age of television Westerns, the Saturdays spent at the matinee, and the simple, clear-cut moral landscapes we learned to navigate. “Prairie Fire” is a reminder that a simple story, well-told, can carry more emotional weight than any elaborate production. It’s a sonic snapshot of a time when the West was truly wild, and a good horse was a man’s only hope for survival. It remains a blazing testament to Marty Robbins’s legacy as the definitive musical voice of the American frontier.