A familiar anthem reborn as a fragile confession under Roy Orbison’s lonely sky

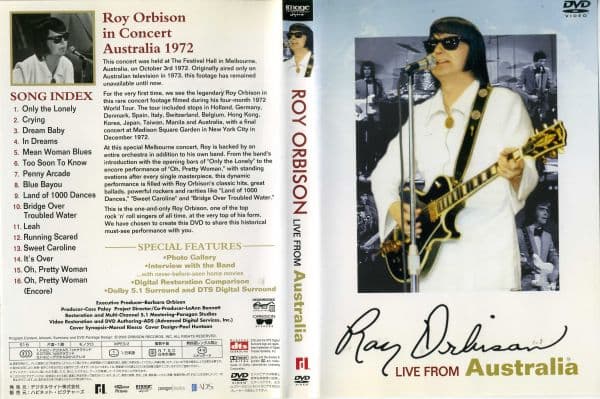

When Roy Orbison stepped onto the Australian stage in 1972 and sang Sweet Caroline, he was not chasing chart positions or radio dominance. The song had already secured its place in pop history years earlier, originally reaching No. 4 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1969 as recorded by Neil Diamond on the album Brother Love’s Travelling Salvation Show. Orbison’s performance, later preserved on Live from Australia 1972, arrived without commercial ambition, yet it stands as one of the most quietly revealing moments of his concert legacy. This was not a hit reborn for the charts, but a classic reinterpreted by a voice that carried its own mythology.

In Orbison’s hands, Sweet Caroline undergoes a subtle but profound transformation. Diamond’s original recording is buoyant, sunlit, and communal, built on forward momentum and an open armed chorus that invites the crowd to sing along. Orbison, however, approaches the song from the interior. His voice does not rush toward celebration. It hovers, restrained and deliberate, as if examining the melody from a distance before stepping inside it. The familiar lyrics about warmth, longing, and emotional arrival feel less like a public declaration and more like a private reckoning.

By 1972, Orbison’s artistic identity was inseparable from vulnerability. His operatic tenor, famous for its soaring climaxes, had always carried a sense of isolation, even at its most powerful. When he sings Sweet Caroline, that quality reframes the song’s emotional center. The joy remains, but it is filtered through reflection. Each line feels weighted by memory rather than anticipation. Where Diamond’s version feels like the beginning of a story, Orbison’s feels like a moment recalled late at night, illuminated by nostalgia rather than daylight.

Musically, Orbison resists embellishment. He does not bend the melody toward excess or dramatize it beyond recognition. Instead, he honors its structure while allowing his phrasing to reshape its meaning. The pauses are longer. The dynamics are more controlled. The effect is intimate, almost confessional, as though he is singing to one person rather than an arena. This restraint is precisely what gives the performance its power. Orbison understood that sometimes the deepest emotional impact comes not from volume, but from vulnerability.

Culturally, this performance stands as a testament to Orbison’s interpretive genius. He had an uncanny ability to step into songs written by others and reveal emotional layers that were always present but rarely foregrounded. Sweet Caroline, often celebrated as a singalong anthem, becomes under his voice a meditation on connection and emotional survival. It reminds us that behind every familiar chorus lies a human story, shaped by who is brave enough to tell it differently.

For listeners who know the song by heart, Roy Orbison’s Australian performance offers something rare. It does not replace the original. It deepens it. In the quiet authority of his voice, Sweet Caroline becomes less about shared celebration and more about the fragile, enduring need to feel close to someone, even if only for the length of a song.