Love That Waits in the Quiet Hours Between Dusk and Regret

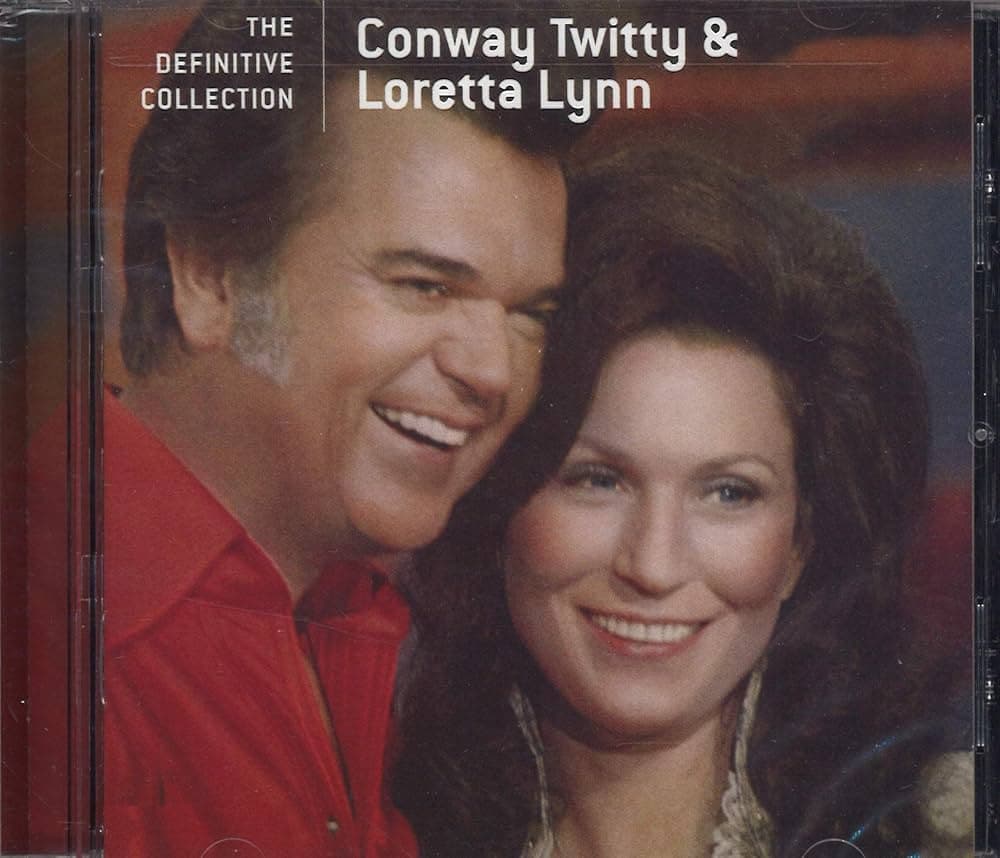

Released in 1973, “From Seven Till Ten” by Conway Twitty and Loretta Lynn emerged during the golden crest of their duet partnership, appearing on their collaborative album Louisiana Woman, Mississippi Man. Though not issued as a major standalone single that stormed the summit of the country charts, it belonged to a period when the pair were virtually synonymous with country radio dominance, repeatedly reaching No. 1 with their joint releases. Within that context, the song carries the weight of an era when their names together guaranteed emotional voltage and commercial force.

By the early 1970s, Conway Twitty and Loretta Lynn had perfected a dramatic chemistry that felt less like performance and more like overheard confession. Their voices did not simply harmonize; they conversed. In “From Seven Till Ten,” that conversational intimacy becomes the engine of the song’s quiet ache. The title itself measures time with almost clinical precision, reducing longing to a three-hour window. Yet within that narrow frame unfolds a universe of secrecy, desire, and moral tension.

The narrative centers on stolen hours. Evening descends, obligations recede, and two voices meet in the fragile space between public identity and private need. Country music has long chronicled infidelity and complicated devotion, but here the emotional architecture is subtler. The arrangement avoids bombast. Instead, it leans into a restrained, almost domestic instrumentation, allowing the vocal interplay to carry the drama. Twitty’s smooth, enveloping tenor suggests reassurance and urgency in equal measure. Lynn’s phrasing, sharp yet vulnerable, injects conscience into the exchange. She does not merely echo him; she challenges the emotional stakes of what they share.

What makes the song endure is not scandal but empathy. The hours “from seven till ten” are not portrayed as reckless abandon. They are tinged with awareness. There is an undercurrent of consequence, an understanding that dawn will come and reality will reassert itself. In that sense, the song reflects a broader strain in 1970s country music, where romantic realism replaced fairy-tale resolution. Love was no longer uncomplicated. It was negotiated, rationed, sometimes hidden.

Their partnership, forged in earlier hits like “Louisiana Woman, Mississippi Man,” had already proven that male-female duets could dramatize both unity and friction. Here, friction softens into shared vulnerability. The song feels less like a courtroom drama and more like a dimly lit kitchen conversation after the children are asleep. The power lies in its restraint.

Listening today, one hears more than a story of clandestine romance. One hears two master interpreters of human frailty. Conway Twitty and Loretta Lynn understood that country music’s greatest strength is its willingness to inhabit uncomfortable truths. In “From Seven Till Ten,” they carve out a small, measured slice of time and fill it with longing that feels both specific and universal. It is a reminder that sometimes the most profound dramas unfold not over years, but in the quiet, ticking hours between evening and regret.