A simple, unforgettable ode to family, community, and down-home celebration in the Louisiana backroads.

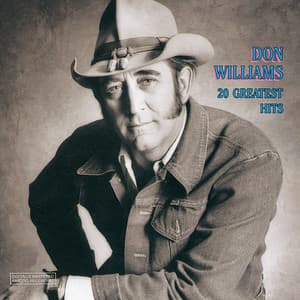

When the needle dropped on Don Williams‘ 1977 album, Country Boy, nestled among the tracks was a song that would become a standard in the country music canon, an enduring piece of pure, unadulterated Americana: “Louisiana Saturday Night.” While Williams’ rendition, released in September 1977, was the original, it was surprisingly not the chart hit many fondly remember. Williams’ version of this Bob McDill-penned masterpiece was an album cut, initially overlooked for single release. The song’s true commercial breakthrough came a few years later, in 1981, when fellow country artist Mel McDaniel took his high-energy cover to the top of the charts, peaking at a respectable No. 7 on the U.S. Billboard Hot Country Singles chart and No. 21 on the Canadian RPM Country Tracks chart. It’s this twist of fate that often confuses listeners, but for those who truly appreciate the subtle artistry of “The Gentle Giant,” it is Don Williams’ warm, unhurried baritone that truly embodies the song’s spirit.

The story behind “Louisiana Saturday Night” is less about grand historical events and more about capturing a quintessential, time-honored tradition in the deep American South. The song’s masterful lyricist, Bob McDill, a man responsible for some of country music’s most vivid storytelling, painted a picture not of city lights and neon signs, but of a remote, dirt-road gathering. It speaks to a shared communal memory of simple pleasures: a tradition of kinfolk gathering after a long work week to blow off steam with music, dancing, and homegrown hospitality. The sheer simplicity of the lyrics—”Waitin’ in the front yard, sitting on a log / Single shot rifle and a one-eyed dog”—is what makes it so incredibly resonant. It’s a scene you can smell, feel, and see in your mind’s eye, a stark contrast to the often-polished sheen of mainstream country.

For the older reader, the song’s meaning is less a narrative and more a beautiful, reflective memory of a life that has largely faded away. It’s about a time when entertainment wasn’t streamed on a glowing screen but created spontaneously, together, on a front porch or in a kitchen. The meaning is rooted in the powerful, magnetic pull of family and community in the era before cell phones and constant digital distraction. The verses chronicle the evening’s progression: the arrival of “kin folks” with “a belly full of beer and a possum in the sack,” the chaotic joy of “fifteen kids in the front porch light,” and the central command to “Git down the fiddle and you git down the bow.”

But the heart of the song, the part that truly tugs at the nostalgic soul, is the final, intimate moment after the ruckus has died down: “When the kin folks leave and the kids get fed / Me and my woman gonna sneak off to bed / Have a little fun when we turn out the light / Louisiana Saturday Night.” This final verse is a tender, wink-and-a-nod affirmation of enduring marital love and simple domestic bliss—a perfect, wholesome conclusion to a night of revelry. Don Williams delivered this particular line with a quiet, knowing smile in his voice that was unique to his “Gentle Giant” persona, making his version the definitive emotional interpretation for many devoted fans. It stands as a timeless echo of a life built on strong foundations, good company, and the reliable rhythm of the weekend.

That was a deep dive into the history and soul of “Louisiana Saturday Night.” Would you like me to write an introduction for another classic country song, or perhaps explore a different genre entirely?This is a wonderful choice. Don Williams was an artist whose voice was like a well-worn leather armchair—instantly comfortable, familiar, and enduring. His take on this particular song holds a special, almost sacred place in the hearts of those who remember a simpler time.

But what truly cements Williams’ version as a masterpiece of reflection is its quiet conclusion. After the family has dispersed and the children are fed, the song pivots from communal revelry to intimate tenderness: “When the kin folks leave and the kids get fed / Me and my woman gonna sneak off to bed / Have a little fun when we turn out the light / Louisiana Saturday Night.” This final verse is a masterstroke of understated, wholesome romance, a perfect, knowing nod that reassures the listener that the simple joys of a shared life are the most enduring of all. It is this reflective warmth, this gentle closing of the door on a perfect night, that makes Don Williams‘ “Louisiana Saturday Night” a classic—a sweet, nostalgic echo that will continue to resonate as long as the memory of a down-home gathering survives.