A Gentle Baritone Turns a Rolling Stone’s Lament into a Meditation on Time and Tenderness

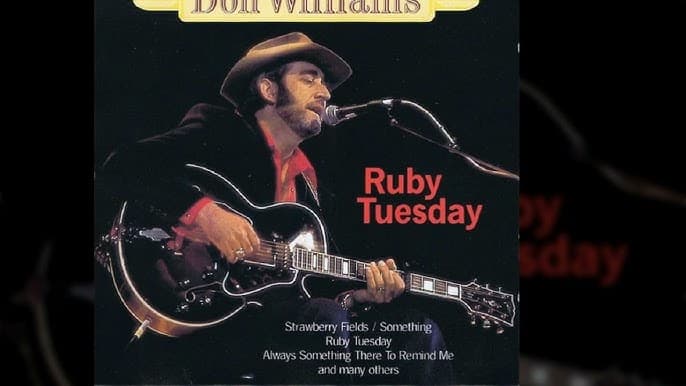

When Don Williams recorded “Ruby Tuesday” for his 1978 album Expressions, he was stepping into the long shadow of a song already immortalized by The Rolling Stones in 1967. Yet his interpretation quietly carved out its own space on the country charts, reaching the Top 10 on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart. In the hands of Williams, a song once framed by baroque pop flourishes and London melancholy was transformed into something earthbound, patient, and unmistakably country.

The original “Ruby Tuesday” had always been a song about transience. Written by Mick Jagger and Keith Richards during a period of romantic instability, it captured the fragile nature of loving someone who cannot be held. The woman at its center is not villainous, nor even distant in the usual sense. She is simply untethered. “Who could hang a name on you?” becomes less a question than an admission of defeat before the inevitability of change.

Williams approached the material with characteristic restraint. His voice, often described as “the Gentle Giant’s” instrument, carried none of the ornate sadness of the original arrangement. Instead, he offered stillness. The tempo is measured, the instrumentation spare. Acoustic guitar and understated steel frame the melody, allowing his warm baritone to do what it always did best: reassure even as it aches. Where the Stones’ version flickers like candlelight in a drafty room, Williams’ rendition feels like dusk settling over open fields.

This is not reinvention for spectacle. It is reinterpretation through temperament. Williams had built his career on songs that honored emotional clarity over drama. In that context, “Ruby Tuesday” becomes less about bohemian mystery and more about the universal human experience of loving someone who cannot remain. His phrasing softens the sharper edges of resignation. There is sorrow here, but also acceptance. The line “Still I’m gonna miss you” sounds less like a wound and more like a vow to remember gently.

The late 1970s were a period when country music often leaned toward polished production and crossover ambition. Yet Williams consistently resisted excess. On Expressions, he maintained the sonic humility that defined his earlier work. By choosing a British rock classic and filtering it through Nashville’s understated craftsmanship, he demonstrated both artistic confidence and interpretive generosity. He did not attempt to outdo the original. He sought to understand it.

In doing so, Williams illuminated something enduring about “Ruby Tuesday.” Beneath its shifting arrangements and cultural associations lies a simple truth: some loves are seasonal. They arrive vivid and unforgettable, then drift onward. Through Williams’ voice, that truth feels neither bitter nor triumphant. It feels lived in.

And perhaps that is why his version lingers. Not because it redefines the song, but because it reminds us that letting go can be as dignified as holding on.