A desert prayer where thirst becomes faith and survival is measured in hope rather than miles

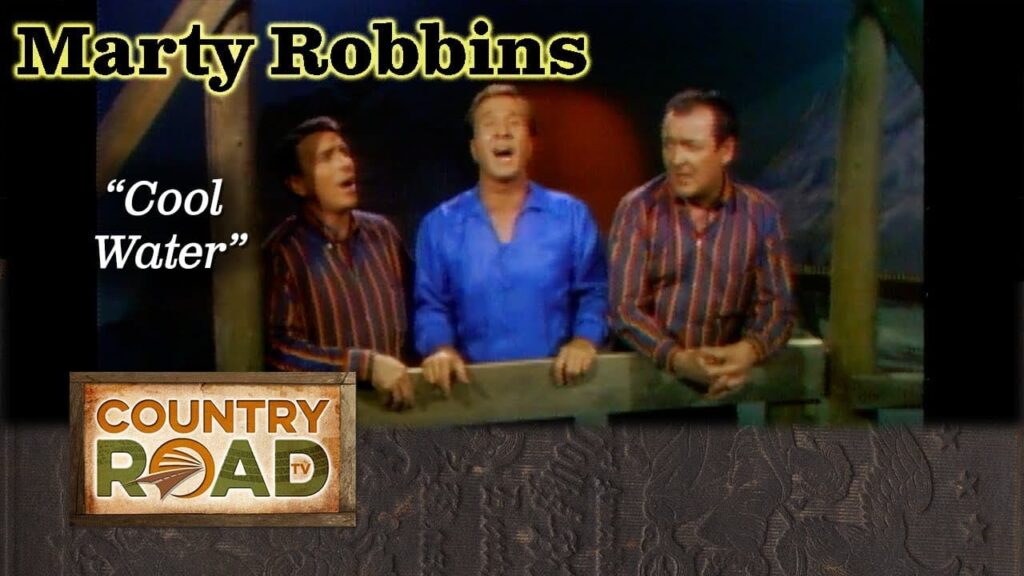

In 1963, when Marty Robbins stepped onto a Nashville stage to perform Cool Water, he was not unveiling a new chart contender so much as reaffirming his place as one of country music’s most literate interpreters of the American West. The song itself had already earned its canonical status decades earlier, first reaching the US pop charts in 1941 in the hands of the Sons of the Pioneers, while Robbins’ own studio association with the piece was firmly tied to his cowboy-era recordings, including All Around Cowboy. By the time of this televised Nashville performance, Robbins was an established hitmaker, a singer whose name routinely occupied Billboard’s country listings, and an artist trusted to carry tradition with dignity rather than nostalgia alone.

Cool Water is not merely a western standard. It is a parable disguised as a trail song, written by Bob Nolan during the Dust Bowl years when thirst was not metaphorical but brutally literal. In Robbins’ hands, the song sheds any hint of camp and becomes something almost spiritual. His voice, famously warm yet controlled, treats the desert not as a romantic backdrop but as a testing ground for the human spirit. Each line feels measured, as if breath itself were a scarce resource. The repeated plea for water is not shouted. It is endured.

What distinguishes Robbins’ 1963 performance is restraint. He understood that Cool Water works best when the singer resists embellishment. There is no operatic swell, no dramatic flourish. Instead, Robbins leans into the song’s conversational cadence, letting silence do part of the work. The pauses between lines suggest heat, exhaustion, and the slow mental unraveling that comes with endless horizon and empty canteen. When the mirage appears, Robbins does not dramatize it. He lets it drift in gently, which somehow makes it more devastating.

Lyrically, Cool Water balances on the edge between hallucination and belief. The narrator’s companion urges him onward, promising relief that may or may not exist. This tension is where Robbins excels. His delivery leaves room for doubt, yet never collapses into despair. The song becomes less about water itself and more about the necessity of belief in motion, in survival, in the idea that endurance is an act of faith.

Culturally, Robbins’ continued return to material like Cool Water during the early 1960s mattered. Country music was modernizing rapidly, absorbing pop structures and urban polish. By performing a song rooted in Depression-era western imagery, Robbins acted as a bridge between eras. He reminded audiences that country music’s emotional authority did not come from novelty, but from memory, landscape, and lived struggle.

In this Nashville performance, Marty Robbins does not sing Cool Water as a relic. He sings it as a living document. The desert still stretches endlessly. The thirst still burns. And the promise of relief, fragile and distant, remains just powerful enough to keep us walking.