A Lone Star’s Lament: A Life Lived on the Range

The enduring ballad of a cowboy’s solitary, yet purposeful, existence.

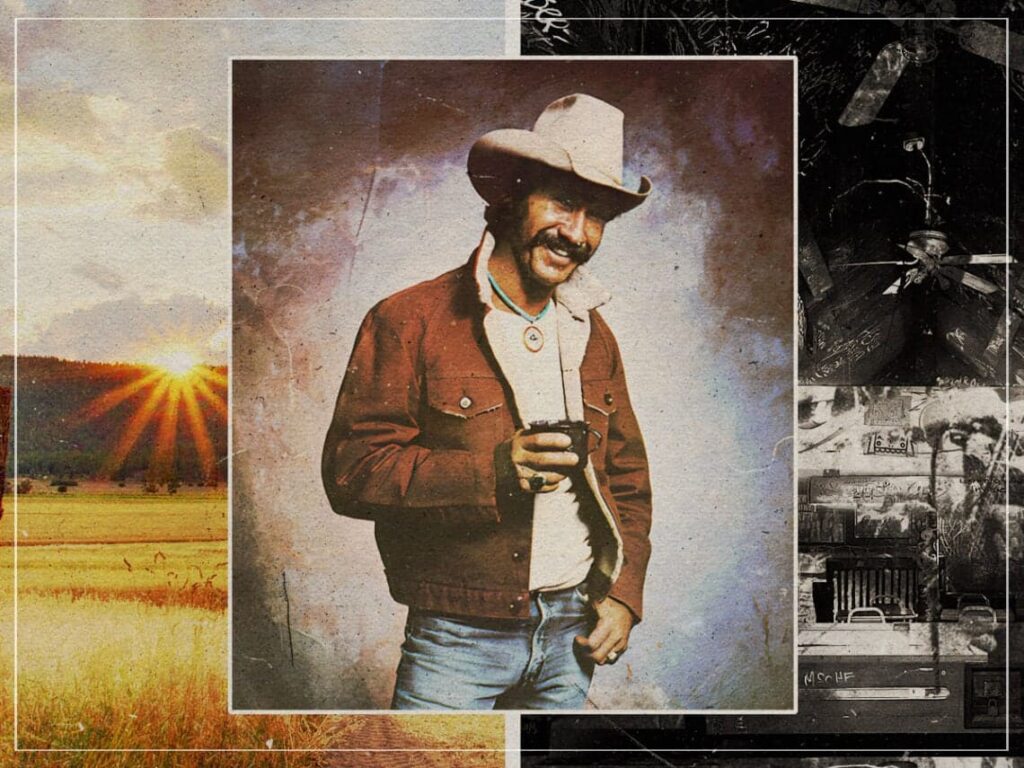

In the vast, untamed landscape of mid-20th century country and western music, few voices resonated with the authentic, storytelling power of Marty Robbins. He was a troubadour of the open range, a poet of the lonesome trail, and his music transported listeners from the comfort of their living rooms to the dusty plains and rugged mountains of the American West. While his legendary song, “El Paso,” is undoubtedly his most famous work, it is perhaps a lesser-known gem, “Doggone Cowboy,” that truly captures the quiet, contemplative soul of the life he so often sang about. This track, a wistful and resolute ode to the cowboy’s lot, first appeared on his 1963 album, Return of the Gunfighter. It’s a song that speaks not of high-stakes duels or tragic love affairs, but of the simple, day-to-day reality of a man who has chosen a life of solitude and hard work.

While “Doggone Cowboy” didn’t chart as a single, its significance lies within the context of the album it was a part of. Return of the Gunfighter was a testament to Robbins’ commitment to the cowboy ballad genre he had so masterfully established with the classic Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs. The album itself was a commercial success, reaching a respectable No. 8 on the Billboard country album chart in 1964, a testament to the enduring appeal of his western narratives. The album showcased Robbins’ unique ability to blend compelling stories with his smooth, melodic voice, making him a perennial favorite for those who longed for a connection to a bygone era.

The story behind “Doggone Cowboy” is less about a specific event and more about a timeless archetype. The lyrics, penned by Robbins himself, are a first-person narrative, a quiet reflection from a man who is “kin to the rovin’ wind.” There’s a profound sense of self-awareness in his words—he knows the life he has chosen is one of endless work, cold nights, and perpetual motion. “I got no home, I got no wife,” he admits, but there’s no hint of bitterness. Instead, there’s a quiet pride. His life, while lonely, is purposeful. He finds meaning in the rhythm of the work: throwing the rope, branding the calf, and moving the herd. The only solace he seems to need is a photograph of a girl, a small, tangible link to a different life he might have had, but ultimately chose not to.

The song’s meaning is a profound exploration of stoicism and independence. It paints a picture of a man who doesn’t complain about the hardships; he simply accepts them as part of his chosen path. The “hot dry wind” and “rain and snow” are not obstacles to be overcome, but simply the backdrop of his existence. He is a man who sings to his herd and is warmed by an old campfire. This isn’t a life of glamor, but one of grit and quiet dignity. For a generation of listeners, particularly those who grew up in rural areas or remembered a time when a man’s word and his work ethic were all he had, this song was a mirror. It was a reminder of the values of self-reliance and the simple satisfaction that comes from a day’s honest labor.

In a world that was rapidly changing, with the rise of rock and roll and the hustle of urban life, Marty Robbins served as a living bridge to the past. His music, and especially a song like “Doggone Cowboy,” felt like a warm, familiar campfire on a cold night. It wasn’t about flashy production or complex arrangements; it was about the raw, heartfelt truth of a story well told. It allowed older listeners to travel back in time, to a place where the stars were bright and the land stretched on forever, and to feel, for a few precious minutes, like a doggone cowboy themselves, master of their own destiny, with nothing but the open road and a deep, abiding sense of purpose.