The ultimate moral of the West: Every legend of the gun is just a man waiting for his last draw.

When we speak of Marty Robbins, the mind inevitably drifts to the high-plains drama of “El Paso” or the stark, unforgettable tension of “Big Iron.” Those towering monuments of Country & Western music rightly define his legacy, yet the true depth of his artistry lies in the other ballads he spun, the lesser-known tales that fleshed out the moral landscape of his imagined West. Among these is a quiet masterpiece of fatalistic storytelling, “The Fastest Gun Around.”

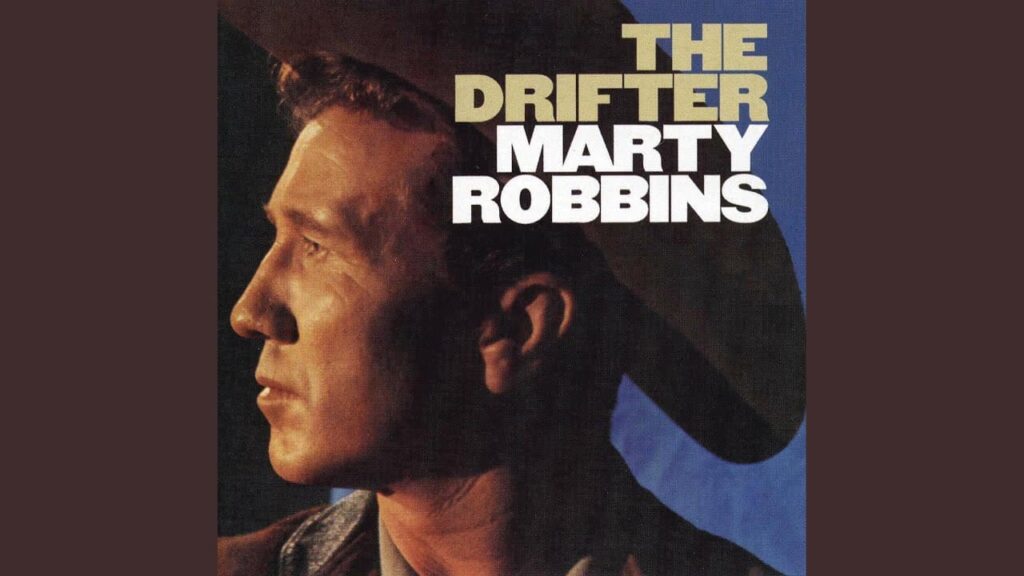

This song hails from a rich period in Marty Robbins‘ career, specifically appearing on his 1963 album, Return of the Gunfighter. This entire record served as a powerful sequel, both thematically and artistically, to the landmark 1959 release, Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs. While the tracks that defined the first album—”El Paso” and “Big Iron”—became massive cross-over hits, charting high on both the Billboard Hot 100 and Country charts, “The Fastest Gun Around” followed a different path. It was an album cut, not released as a promotional single in the United States, and therefore it did not earn a traditional chart position on the major pop or country singles lists. It was a deep track, a testament to the fact that the album format, in the hands of a master storyteller like Robbins, could hold more than just chart-bait. Its commercial success was entirely bound up in the enduring appreciation for the album genre it represented, cherished by an audience devoted to the Western narrative.

The song, a composition by J. Pruett and J. Glaser, is a pristine example of the “Gunfighter Ballad” genre that Marty Robbins virtually invented. Unlike the romantic tragedy of “El Paso,” or the heroic justice of “Big Iron,” “The Fastest Gun Around” is a bleak, stripped-down parable on the curse of celebrity and the inevitability of fate. The story is told in the third person, chronicling a man who has achieved the coveted, yet fatal, title of the fastest gun. The world watches him, not in awe, but with the cynical knowledge that his reign is purely temporary.

The meaning of the song resonates far beyond the dust and tumbleweeds. It captures the sheer burden of being at the very top, of the crushing weight of expectation and the constant threat that comes with absolute superiority. “He rides alone and seldom speaks, the price is too high to pay,” the lyrics confess, painting a picture of a man isolated by his own skill. For the older listener, this tale taps into a universal truth: that fame, and the constant need to defend it, drains the soul. It reflects on how the very nature of an accomplished life breeds challengers, and that even the greatest among us are ultimately victims of a world that demands a faster, younger replacement. The climax, which arrives with startling suddenness and simplicity, underscores the song’s core theme: the fastest man alive is only so until the moment he isn’t.

It is this profound, existential loneliness that makes “The Fastest Gun Around” such a compelling piece to revisit. The spare, acoustic arrangement, characteristic of the Gunfighter Ballads era, allows Robbins‘ rich, warm voice and impeccable, unhurried delivery to carry the full weight of the tragedy. He was never just singing a song; he was performing a miniature radio play, allowing us to feel the quiet desperation of the man whose skill has become his prison. This ballad, while perhaps overlooked by the casual listener, is essential for understanding the true genius of Marty Robbins—a man who used the simple, direct idiom of country and western to explore the timeless, complex philosophies of power, isolation, and mortality. It’s a reflective lament for every champion, and a nostalgic reminder that even in the grand legends of the Wild West, the bravado eventually runs out, and all that remains is the echoing sound of the final shot.