Where a Cowboy Rides No More: The Ballad of Regret and the Final Request

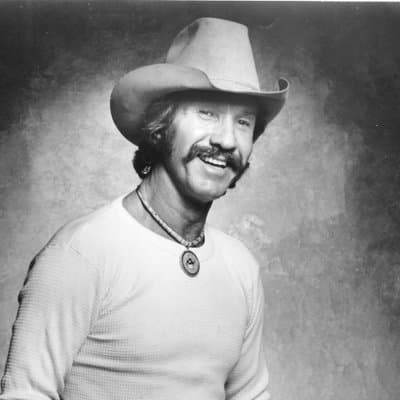

For those of us who grew up listening to the resonant baritone of Marty Robbins on the radio, spinning tales of the Old West that were more compelling than any Hollywood picture, few songs evoke a deeper, more reflective melancholy than “The Streets of Laredo.” It’s a track that feels less like a piece of popular music and more like an echo from a dusty, forgotten time.

Robbins’ rendition of the traditional folk standard was released on July 18, 1960, as part of his seminal sequel album, More Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs. While it didn’t chart as a single—it was a traditional ballad and part of an album, unlike his smash hits “El Paso” and “Big Iron” from the first Gunfighter Ballads volume—it cemented his reputation as the premier balladeer of the American West. The 1960 album itself, More Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs, was highly regarded, being voted No. 9 among the “Favorite C&W Albums” of 1960 in Billboard magazine’s annual poll of country music disc jockeys, demonstrating the high esteem in which this music was held by the country audience.

The immediate story of “The Streets of Laredo” is simple, heartbreaking, and instantly unforgettable: the narrator, a lone cowboy, encounters a younger cowboy “wrapped up in white linen, and cold as the clay,” clearly dying from a gunshot wound to the breast. The dying man recounts his tale of woe, lamenting how his good life of riding gave way to the pitfalls of town life—drinking, card-playing, and frequenting dance halls. The song is the dying man’s last testament, detailing a heartbreakingly specific funeral request: “Get six jolly cowboys to carry my coffin, / Six dance-hall maidens to bear up my pall,” and the instruction to “Beat the drums slowly, and play the fife lowly,” a somber request for a military-style funeral march.

What makes the song’s meaning so rich and layered is its incredible backstory. “The Streets of Laredo,” also widely known as “The Cowboy’s Lament,” is an American adaptation of a much older European folk song, tracing its lineage back to the 17th or 18th century, primarily through the Irish ballad “The Unfortunate Rake.” This detail changes the song’s texture profoundly. In the original British versions, the young man was not dying from a quick, romantic gunshot, but from a venereal disease—a much slower, more agonizing, and less glamorous fate brought on by a reckless lifestyle with “flash-girls.” The American version wisely, perhaps, softened the tragic cause of death to a more acceptable—and heroic, in the Western context—bullet wound, preserving the emotional core of regret while adapting it for the new world.

Marty Robbins brought this centuries-old cautionary tale to a new generation, weaving its sorrow into the fabric of the romantic Western mythos. The ultimate meaning of “The Streets of Laredo” is a universal one: it’s a lament for wasted youth and the price paid for an undisciplined life. The dying cowboy’s final requests—for the jolly cowboys and the dance-hall maidens—aren’t just poetic flourishes; they are a profound, desperate cry for validation. He wants the very people who witnessed his downfall to grant him a moment of respect in death. He’s asking his comrades to remember him, not just as the fool who got “cut down in his prime,” but as a man worthy of ceremony, however tragic.

For those of us reflecting on the passage of time, the song is a powerful memento mori—a reminder of the choices made and the paths not taken. The waltz-like 3/4 time signature that defines the melody, an almost cruelly gentle tempo for such a dark topic, makes Robbins’ version feel like a slow, deliberate march towards the grave, an emotional pull that remains as strong today as it was in 1960. It stands as a timeless classic, ranked as one of the Top 100 Western songs of all time by the Western Writers of America, a legacy secured by the heartfelt, earnest voice of the great Marty Robbins.