A Farewell Hung Between Twilight and Silence

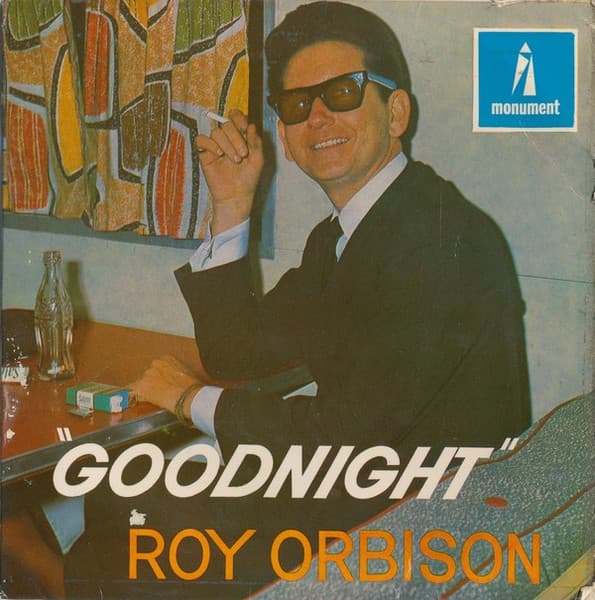

Released in early 1965 as a single by Roy Orbison, Goodnight slipped into the public ear as a quiet, elegiac whisper rather than a bombastic anthem — yet it reached respectable chart positions: peaking at No. 21 on the US Billboard Hot 100 and climbing to No. 14 on the UK Singles Chart. Though overshadowed by its predecessor “Oh, Pretty Woman,” the song occupies a tender, haunting place in Orbison’s catalogue, capturing a grief-tinged farewell on the cusp of his transition from teen-idol rockabilly to more introspective, orchestral balladry.

From the first breath of its melancholic melody — constrained within a modest 2:23 runtime on the 7″ single release. — Goodnight reveals a soul at odds with its own longing. The lyrics unfold with agonized serenity: “My lovely woman child / I found you out running wild with someone new,” he begins. The betrayal is not shouted, but spoken — each syllable weighted, each “goodnight” a resignation heavy with sorrow. As the song advances, listeners realize this is not mere heartbreak, but a slow, inevitable farewell — not just to a lover, but to the conjured illusions of love itself.

Musically, Orbison and co-writer Bill Dees (credited as composer alongside Orbison) fashion a composition that refuses dramatic flourishes. Instead, it unfolds through subtle shifts: a minor-toned chord here, a swelling string hint there, all designed to cradle Orbison’s voice — that remarkable instrument of tremolo and pain — in a bed of quiet dread. The song eschews hooks or anthemic choruses; its emotional power lies in understatement — in the weight of absence, and the finality of simple parting words.

In the story of Orbison’s career, Goodnight stands as a bridge. It followed the worldwide phenomenon of Oh, Pretty Woman, a record so successful it cast a long commercial shadow. Yet with Goodnight, Orbison was already turning inward — toward the kind of songwriting and performance that would define his later ballads: introspective, emotionally layered, and unafraid of grief. Indeed, some contemporaneous observers speculated that the record’s multi-section structure — shifting melodies, tonal phases, and a compact but complex architecture — may have worked against it commercially.

But perhaps that is precisely what makes Goodnight enduring. It is not a crowd-pleaser. It does not demand that you sing along. Instead, it asks that you listen deeply — to heartbreak whispered, to love lost in shadow, to the hollow echo that remains once all the lights have dimmed. In that quiet space between spoken lyric and fading chord, Orbison transforms a simple word — “Goodnight” — into a door closing on a dream.

For listeners attuned to fullness of sorrow and subtlety of sorrow, Goodnight remains a testament: that not all goodbyes must be loud; some are heard only in the silence that follows.