A raw declaration of defiance and desire, where youthful bravado collides with the restless heart of early rock and roll.

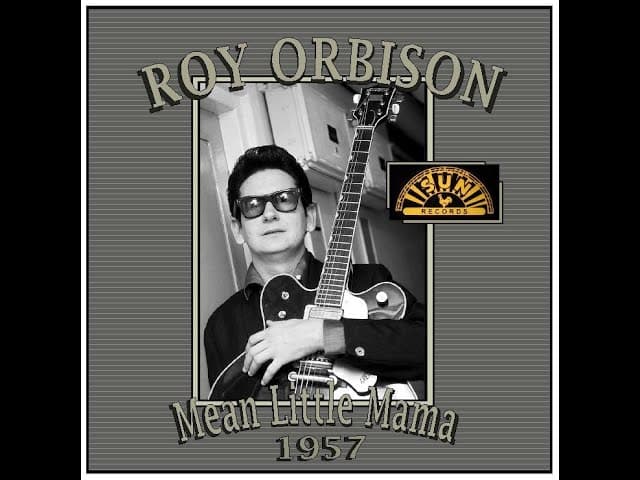

Released in 1958 by Roy Orbison, Mean Little Mama arrived during his formative Sun Records period, issued as a standalone single rather than as part of a contemporary studio album and later preserved on archival collections of his Sun era recordings. Upon release, the song did not secure a position on the major national charts, yet its lack of commercial traction obscures a more revealing truth. This recording captures Orbison at a critical crossroads, still untethered from the operatic ballads that would later define his legacy, but already marked by an intensity and emotional clarity that set him apart from his peers.

Mean Little Mama is steeped in the language and posture of late 1950s rock and roll, a genre still asserting its identity against polite pop and fading swing traditions. The song’s narrator speaks with swagger and wounded pride, addressing a woman whose power lies not in tenderness but in provocation. Rather than romanticizing devotion, the lyric centers on friction, a push and pull that feels physical and immediate. This is not love as destiny. It is love as confrontation. Orbison delivers the vocal with a clipped urgency, favoring rhythm and bite over the sustained, cathedral like phrasing that would later become his signature.

Musically, the track reflects Sun Records’ stripped down aesthetic. The arrangement is lean and percussive, driven by a churning groove that leaves little room for ornamentation. The production places Orbison squarely in the room with the listener, his voice unvarnished and direct. What is striking in retrospect is how controlled his performance already is. Even within this rougher framework, Orbison resists excess. He understands tension, when to press forward and when to hold back, an instinct that would later allow him to turn heartbreak into something almost mythic.

The emotional core of Mean Little Mama lies in its honesty. There is no plea for mercy, no illusion of redemption. The woman at the center of the song is admired and resented in equal measure, a figure who commands attention by refusing to yield. In this sense, the song mirrors the emotional landscape of youth itself, where desire often arrives tangled with frustration and pride refuses to soften into vulnerability. Orbison does not ask for sympathy. He stands his ground, even as the undercurrent of longing remains unmistakable.

In the broader arc of Roy Orbison’s career, Mean Little Mama functions as a revealing artifact. It documents an artist still shaped by the raw energy of Southern rock and roll, yet already searching for a deeper expressive language. While later classics would elevate him to near operatic grandeur, this early recording reminds us that his artistry was built first on grit, rhythm, and emotional nerve. For listeners willing to look beyond chart positions and familiar hits, Mean Little Mama offers a compelling glimpse of a young voice learning how to command the darkness it already knew so well.