Voice standing alone in the dark, confessing that heartbreak has a sound and it sings in falsetto.

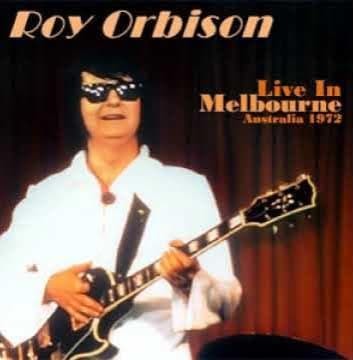

When Roy Orbison first released Only The Lonely in 1960, the record did something rare even by Monument Records standards. It climbed to No. 2 on the US Billboard Hot 100 and reached No. 1 in the United Kingdom, announcing Orbison as a singular emotional force rather than just another rock and roll singer. The song appeared on his album Lonely and Blue, a collection that crystallized his early artistic identity. By the time Orbison performed Only The Lonely (Live From Australia, 1972), the song was no longer a new hit chasing chart positions. It was a settled truth. A confession refined by time, loss, and lived experience.

The song itself was born from rejection and persistence. Written by Orbison with Joe Melson, Only The Lonely was initially turned down by Elvis Presley and the Everly Brothers, both unsure how to inhabit its exposed emotional register. That refusal proved essential. The song demanded a singer who could stand still and let vulnerability do the work. Orbison understood that the drama was not in volume or bravado but in restraint. The arrangement is sparse yet deliberate. A measured beat. Soft backing vocals that sound like distant witnesses. Then the voice rises, not to impress, but to survive.

Lyrically, Only The Lonely is deceptively simple. It does not rage against heartbreak or bargain with it. Instead, it accepts solitude as a condition, almost as a private club whose members recognize each other by pain alone. The narrator is not asking for sympathy. He is naming a state of being. Loneliness here is not fleeting sadness. It is identity. Orbison sings as if he has already passed through denial and anger and arrived at something quieter and more permanent.

The 1972 Australian performance reveals how deeply the song had fused with Orbison’s persona. By this point in his life, he had endured personal tragedies that reshaped the emotional weight of his catalog. When he sings Only The Lonely on stage in Australia, the voice is still technically precise, but the edges are darker, heavier. The famous falsetto no longer sounds like youthful heartbreak. It sounds like memory. Each sustained note carries the sense of a man who knows that loneliness does not end when applause begins.

Musically, the live arrangement remains respectful to the original structure. There is no attempt to modernize or dramatize it beyond recognition. Orbison understood that this song required space. Silence matters. Pauses matter. The audience listens not because they are being entertained, but because they are being addressed. In that moment, the concert hall becomes intimate. Thousands of people are invited into a confession that feels singular and private.

Culturally, Only The Lonely stands as one of the defining statements of Orbison’s legacy. It helped create a new archetype in popular music. The fragile male narrator. The operatic pop ballad that refuses irony. Decades later, the song endures not because it represents its era, but because it escapes it. In the Australian performance, you can hear that truth clearly. This is not nostalgia reenacted. This is a song still alive, still aching, still standing alone in the dark, singing because silence would hurt more.