A quiet vow of devotion, where love is not shouted but patiently endured in the shadows.

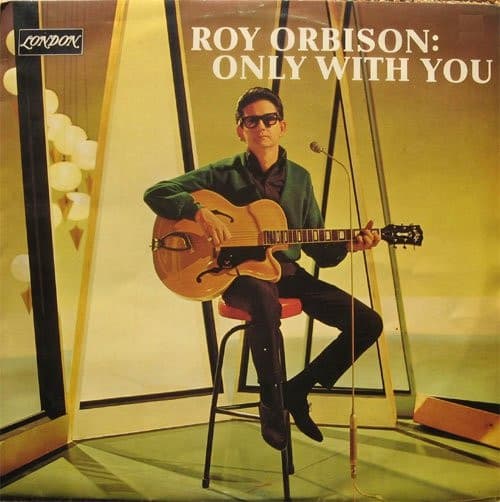

Upon its release in 1960, Only With You by Roy Orbison entered the American singles charts with a restrained presence, reflecting its intimate scale rather than mass spectacle. Issued during Orbison’s early tenure with Monument Records and later included on the album Lonely and Blue, the song arrived at a pivotal moment, when Orbison was still shaping the emotional architecture that would soon define his most towering work. It did not storm the charts the way his later classics would, but it announced something just as important: a singular voice learning how to make vulnerability sound monumental.

The power of Only With You lies not in dramatic confession, but in emotional precision. This is Orbison before the operatic crescendos, before the mythic loneliness of his best known hits, choosing instead to sing in half lights. The narrator does not plead or protest. He simply states a truth that feels unavoidable. Meaning exists only in the presence of one other person. Without her, the world dims into something barely navigable. That emotional premise is simple, yet Orbison treats it with reverence, allowing silence and restraint to do as much work as melody.

Musically, the song is built on a gentle, almost suspended structure. The arrangement avoids ornamentation, leaving wide open spaces around Orbison’s voice. This sparseness is crucial. It mirrors the lyrical dependency at the heart of the song. Everything feels contingent, held together by a single emotional thread. When Orbison sings, his phrasing stretches just slightly behind the beat, creating a sense of hesitation, as if each line must be carefully weighed before being released into the air. It is a performance rooted in control, not excess.

Lyrically, Only With You explores devotion without illusion. There is no promise of triumph or permanence, only an acknowledgment that love has reordered the singer’s inner world. Orbison does not portray himself as strong because of love, but exposed by it. This perspective would become central to his artistic identity. Even here, early in his Monument catalog, he is already dismantling the traditional masculine posture of pop music. He allows longing to sound fragile, even dependent, without apology.

In the broader arc of Orbison’s legacy, Only With You functions like a quiet sketch that reveals the contours of a masterpiece yet to come. You can hear the emotional grammar he would later refine. The sustained notes that hover between hope and despair. The refusal to resolve feelings neatly. The sense that love, once admitted, becomes an irreversible condition.

For listeners willing to lean in, the song offers a rare intimacy. It is not designed to overwhelm. It waits. And in that waiting, Roy Orbison shows how a soft voice, anchored in truth, can linger just as powerfully as any operatic cry.