A young voice straining against distance and doubt, already revealing the ache that would define a legend

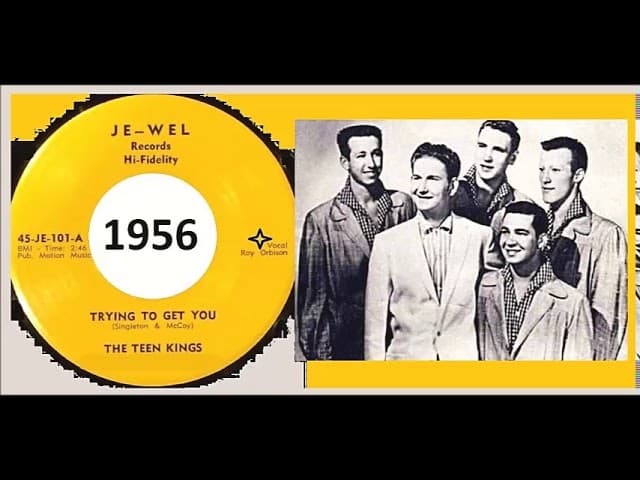

Released in 1956 as a Sun Records single by Roy Orbison & The Teen Kings, Trying To Get To You did not register on the national charts upon its initial appearance, yet its absence from the listings tells only a fraction of the story. The song later found a lasting home on At the Rock House, the 1961 album that gathered Orbison’s early Sun sides and preserved them as the raw foundation of an extraordinary career. Long before stadiums, operatic climaxes, or chart topping ballads, this recording captures Orbison at the moment his artistic identity first begins to surface.

Trying To Get To You is not polished in the way listeners would later expect from Orbison. Instead, it is urgent, almost breathless, built on the rhythmic snap and echo laden space that defined Sun Records in the mid 1950s. What makes it remarkable is how fully formed his emotional instincts already were. Even within the conventions of early rock and roll, Orbison’s voice refuses to stay casual. It reaches, strains, and pleads. The title itself is deceptively simple, but the performance suggests obsession rather than romance, pursuit rather than courtship. This is not a song about love found. It is about love just beyond reach, a theme that would haunt much of his later work.

Lyrically, the song is direct, even repetitive, yet that repetition becomes its emotional engine. Each return to the central phrase feels less like a chorus and more like a confession that cannot be contained. Orbison sings as though motion itself were emotional, as if the act of trying carries more weight than the destination. This sense of longing without resolution would later become a signature, but here it appears in its earliest and most vulnerable form. There is no grand tragedy yet, only restless yearning, but the seeds are unmistakable.

Musically, the track sits at a crossroads. The Teen Kings provide a steady, driving framework rooted in rockabilly tradition, while Orbison’s vocal phrasing hints at something more dramatic, almost theatrical. He bends notes in ways that resist the song’s simplicity, stretching phrases beyond their expected shape. It is the sound of an artist pushing against the limits of the form he has been given. Sun Records was known for capturing spontaneity, and this performance feels captured rather than constructed, a moment preserved before refinement set in.

Culturally, Trying To Get To You stands as a document of transition. It belongs to the era when rock and roll was still discovering its emotional vocabulary. Orbison would later expand that vocabulary immeasurably, but this song matters because it shows the first articulation of his inner world. The charts may have overlooked it, but history did not. In retrospect, the recording feels like a quiet declaration of intent. Roy Orbison was already singing not just to be heard, but to be understood.