A heartbreak disguised as laughter, where sorrow paints its face and smiles learn to ache.

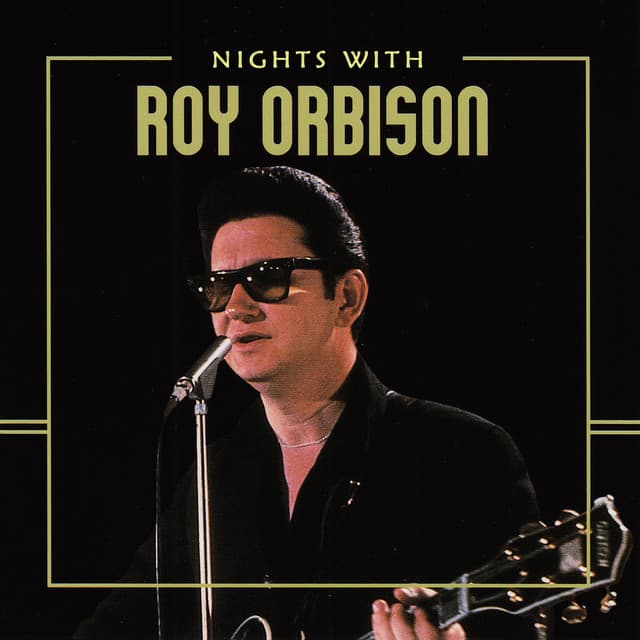

Released during the early Monument Records years of Roy Orbison, The Clown emerged in 1962 on the album Roy Orbison Sings Lonely and Blue, and was issued on vinyl as the B side to Candyman, a single that rose into the Top Ten in the United States and reached the upper tier of the British charts. While the spotlight belonged to its companion track, The Clown occupied a quieter space, one that longtime listeners and collectors would come to recognize as central to Orbison’s emotional vocabulary. It stands not as a commercial statement, but as a deeply revealing one, etched into the grooves of an album that defined his early artistic identity.

At its core, The Clown is a study in emotional concealment. Orbison does not merely sing about sadness. He dramatizes the performance of happiness itself. The narrator adopts the image of a clown, a figure whose purpose is to entertain, distract, and reassure, even while heartbreak tightens behind the greasepaint smile. This metaphor aligns seamlessly with Orbison’s recurring themes of loneliness and emotional isolation, yet it feels particularly intimate here. The song does not rage or plead. It accepts its role with quiet resignation, turning suffering into a kind of private ritual.

Musically, The Clown reflects Orbison’s early stylistic restraint. Before the operatic crescendos that would later define his signature sound, this recording relies on controlled phrasing and subtle arrangement. The tempo moves deliberately, allowing each line to linger. Orbison’s voice, already unmistakable, carries a fragile steadiness. There is no melodrama in his delivery. Instead, there is dignity. Pain is not shouted. It is worn, carefully, like a costume that must remain intact no matter how heavy it becomes.

Lyrically, the song speaks to a universal emotional truth that transcends era and genre. Many listeners recognize themselves in this figure who laughs on cue and cries alone. Orbison understood that heartbreak often operates in silence, especially when love has ended without spectacle. The Clown captures the moment after the damage is done, when life continues and the performance must go on. In this way, the song feels less like a confession and more like an observation, delivered with empathy rather than self pity.

Within the broader context of Roy Orbison Sings Lonely and Blue, The Clown plays a vital role. It bridges Orbison’s rockabilly roots with the emotional balladry that would soon make him singular in popular music. This is the sound of an artist refining his emotional language, learning how to let vulnerability speak without excess.

For the vinyl listener, The Clown rewards patience. It reveals itself slowly, like many of Orbison’s most enduring works. It may never have claimed chart dominance under its own name, but its legacy lives where it matters most, in the quiet recognition of those who understand that sometimes the saddest songs are the ones that smile first.