Man Watches Love Slip Through His Hands and Learns the Sound of Irreversible Goodbye

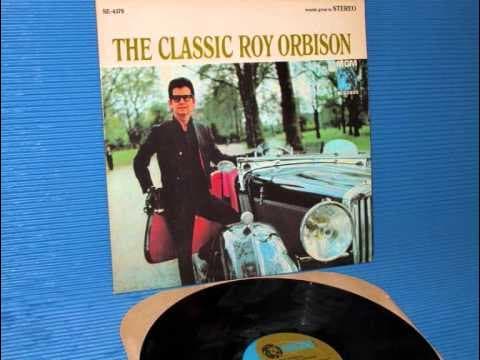

When Roy Orbison released “Losing You” in 1963, it ascended to No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100, further cementing his reign as one of the era’s most distinctive and emotionally formidable voices. Issued as a single and later included on the album In Dreams, the song stood comfortably among the run of dramatic, operatic ballads that defined Orbison’s early 1960s output. By this point, he was no longer simply a hitmaker; he was an architect of heartbreak, shaping popular music with a tenor that could tremble, soar, and fracture in a single breath.

Written by Roy Orbison and Joe Melson, “Losing You” inhabits that peculiar emotional territory where denial and realization coexist. The song does not erupt into melodrama. Instead, it unfolds with a restrained ache. Orbison’s narrator is not raging against betrayal nor begging for reconciliation. He is listening to the quiet evidence of departure. The footsteps recede. The warmth fades. The truth arrives gently but definitively.

Musically, the arrangement is classic early-1960s Monument Records craftsmanship. The rhythm is steady, almost deceptively calm, while strings and backing vocals rise like distant weather on the horizon. Orbison’s voice enters not as a shout but as a confession. He begins in a register that feels conversational, even controlled. But as the song progresses, the emotional voltage increases. When he ascends into his upper register, that unmistakable, keening cry, it feels less like performance and more like revelation. This is not theatrical sorrow. It is a man discovering that love’s departure has already happened.

What distinguishes “Losing You” within Orbison’s catalog is its subtlety. Unlike the cinematic sweep of “Running Scared” or the dreamlike desolation of “In Dreams,” this song is grounded in a more domestic heartbreak. There are no elaborate metaphors or surreal images. The lyrics are direct, almost plainspoken. That simplicity is its strength. It captures the universal moment when one partner senses the emotional withdrawal of the other long before the final words are spoken.

Culturally, the track reinforced Roy Orbison’s reputation as a singular presence in early rock and roll. At a time when many male vocalists leaned into bravado or charm, Orbison offered vulnerability without irony. He stood still, dressed in black, dark glasses shielding his eyes, and sang about fear, doubt, and longing. “Losing You” became another chapter in that quiet revolution, proving that masculinity in pop music could be tender, wounded, and profoundly introspective.

More than six decades later, the song remains a study in emotional inevitability. It reminds us that some endings do not arrive with slammed doors. They arrive softly, in the silence between two people. And in that silence, Roy Orbison found one of his most enduring truths.