Man Drives South, Chasing a Memory He Can Never Outrun

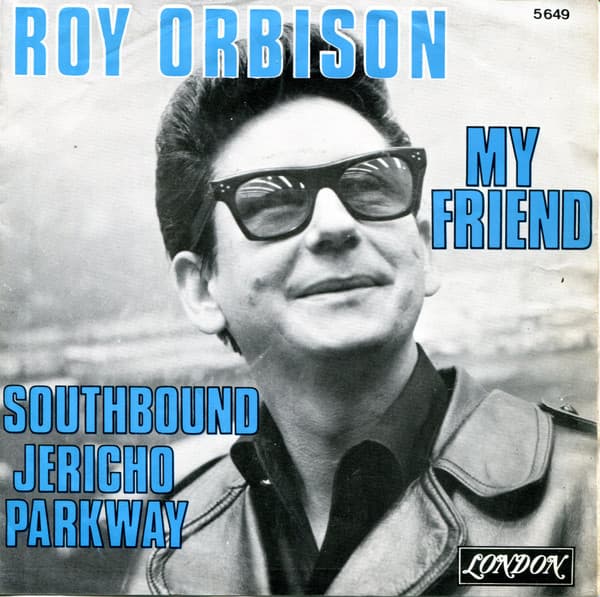

When Roy Orbison released “Southbound Jericho Parkway” in 1969, it arrived not as a chart-topping spectacle but as a quiet, contemplative statement nestled within the album The Big O. The record itself marked a subtle turning point in Orbison’s late-1960s output, reflecting an artist navigating shifting musical tides while remaining fiercely loyal to his own operatic sensibilities. Though the single did not achieve the towering commercial heights of his early 1960s classics, its placement on the album signaled something far more intimate: a retreat into narrative, into character, into the lonely interior landscapes where Orbison’s voice had always felt most at home.

By 1969, the British Invasion had long redrawn the pop map. Rock was louder, more political, more psychedelic. Yet Orbison, ever the solitary romantic in black, chose a different road. “Southbound Jericho Parkway” is not merely a song about travel; it is a meditation on displacement. The title itself evokes movement, geography, and inevitability. A man driving south. A direction that suggests descent, heat, reckoning.

The narrative unfolds with cinematic restraint. Orbison does not rage. He does not accuse. Instead, he inhabits the quiet devastation of a father separated from his child, tracing the emotional distance mile by mile. The parkway becomes both literal highway and metaphoric exile. Few singers could render such restrained anguish without slipping into melodrama. Orbison, with that cathedral-like tenor rising from a whisper to a cry, makes the pain feel dignified. Controlled. Almost holy.

Musically, the track resists the bombast that defined much of his earlier Monument recordings. The orchestration is measured, allowing space for phrasing and breath. The arrangement swells but never overwhelms. It mirrors the song’s emotional architecture: longing contained within composure. There are no operatic crescendos of romantic ecstasy here, only the steady hum of resignation.

What makes “Southbound Jericho Parkway” endure is not spectacle but empathy. Orbison’s gift was always his ability to universalize solitude. He sang as if heartbreak were a private confession overheard by millions. In this song, that gift is distilled to its essence. The protagonist does not seek revenge or redemption. He simply drives. And in that motion lies the tragedy.

For an artist so often associated with grand, sweeping balladry, this song reveals another facet of Roy Orbison: the chronicler of quiet departures. The man who understood that sometimes the most devastating journeys are not the ones we choose, but the ones we must endure.