A Voice from the Shadows, Reaching Toward an Unattainable Light

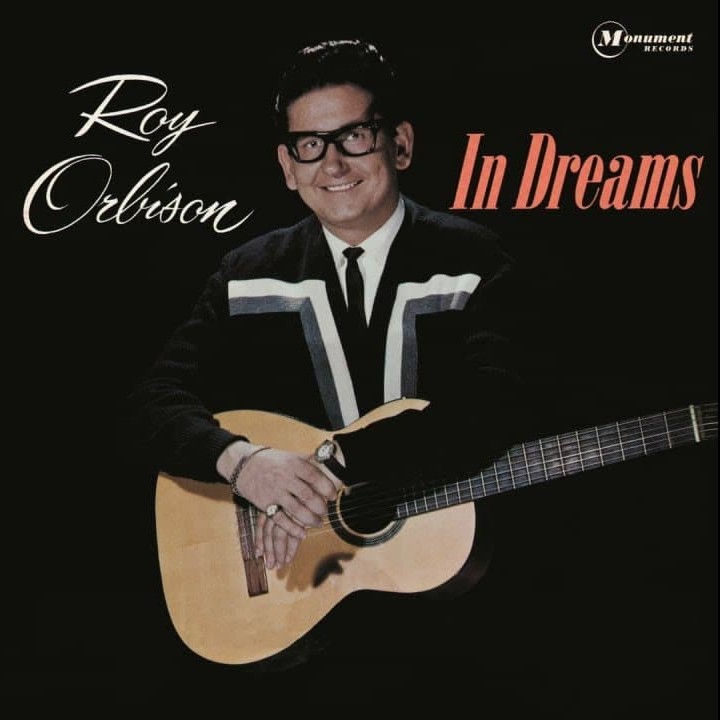

When Roy Orbison released “Beautiful Dreamer” in 1963 as a single on Monument Records, it did not storm the upper reaches of the Billboard charts in the way “Oh, Pretty Woman” or “Only the Lonely” would soon do. Instead, it settled modestly within the Hot 100, a quieter entry in a year crowded with hits, and was later included on the album In Dreams. Yet chart positions often fail to measure what truly matters in Orbison’s catalog. Some songs blaze; others linger like twilight. “Beautiful Dreamer” belongs to the latter.

The title evokes the 19th-century standard by Stephen Foster, but Orbison’s composition is an entirely different reverie. Where Foster’s piece drifts on parlor-room sentimentality, Orbison’s version carries the ache of distance, the tension between longing and inevitability. It is less a serenade than a confession whispered into the dark.

By 1963, Orbison was refining a singular aesthetic: operatic vulnerability wrapped in the architecture of pop. His voice, that improbable instrument capable of spanning from tremulous baritone to piercing falsetto, becomes the emotional engine of the song. The arrangement is deceptively restrained. A steady rhythm section grounds the piece, while the melody ascends in slow, deliberate arcs. The effect is cinematic without excess, a hallmark of the Monument sound under producer Fred Foster.

Lyrically, “Beautiful Dreamer” is about the fragile hope that survives even when love seems fated to dissolve. Orbison does not plead in the direct, earthbound manner of many early-1960s rock ballads. Instead, he frames his beloved as something almost ethereal, a figure glimpsed through memory or imagination. The dreamer is both present and unreachable. This duality gives the song its quiet tension. It is the sound of a man aware that desire alone cannot secure permanence.

What makes the performance enduring is Orbison’s control of emotional escalation. He does not rush toward the climactic high notes. He approaches them as if ascending a staircase, step by aching step. When the falsetto finally blooms, it is not triumphant. It is fragile, almost translucent. The listener senses that the dream may shatter at any moment.

Within the broader arc of Roy Orbison’s career, “Beautiful Dreamer” sits between seismic cultural shifts. The British Invasion was gathering force. Rock was becoming louder, brasher, more rebellious. Orbison, clad in black and shielded by dark glasses, offered something paradoxically bold: sincerity without irony. In that context, “Beautiful Dreamer” feels like a final candle burning before the storm.

Today, revisiting the track reveals its subtle craftsmanship. It is not built on spectacle but on atmosphere. It does not demand attention; it invites it. And in that invitation lies its power. The dreamer may be elusive, but the emotion is undeniable. Orbison understood that sometimes the most profound declarations are not shouted from rooftops. They are sung softly, in the key of longing, to someone who may already be fading into sleep.