A song of regret, confinement, and the ghostly whistle of freedom

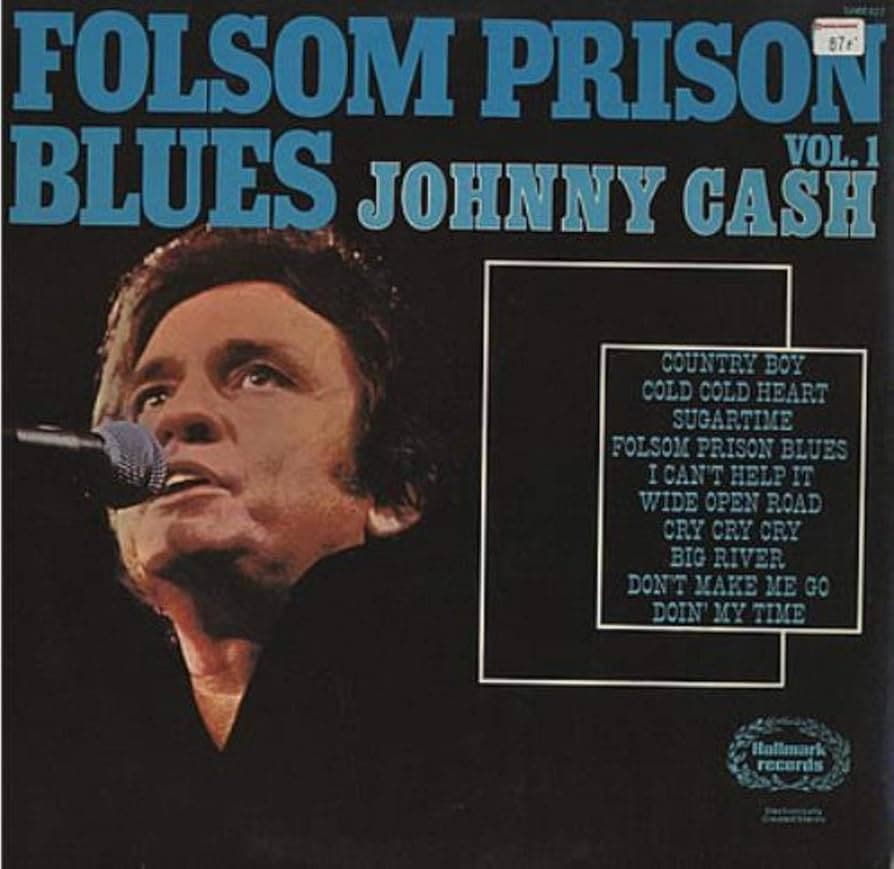

When Johnny Cash first released “Folsom Prison Blues” in 1955, it quietly became one of his signature numbers — a song that captures longing, remorse, and the toll of isolation. The original studio version peaked at #4 on the Billboard Country & Western Best Sellers chart in early 1956.

From the opening chord, “Folsom Prison Blues” sets the listener inside a cell, not of concrete immediately, but of memory and conscience. The narrator lies behind bars, hearing the train whistle in the distance, thinking of all the freedoms lost, of the world beyond the walls. There’s the famous, chilling line: “But I shot a man in Reno / Just to watch him die.” It’s not just violence, but cruelty, existential despair — this act becomes a mirror for guilt, detachment, and a hell of one’s own making.

Johnny Cash wrote “Folsom Prison Blues” around 1953, while serving in the United States Air Force, stationed in West Germany. During this time, he saw the film Inside the Walls of Folsom Prison. That movie, with its depiction of prison life, made a strong impression on him — the stories of men locked away, the sense of loss and longing, all of it struck Cash deeply.

The melody and parts of the lyrics drew from Gordon Jenkins’s “Crescent City Blues” (1953), a song that Cash heard and borrowed from, sometimes heavily, for structure and mood. This borrowing later led to legal settlement, once “Folsom Prison Blues” had become very popular.

The initial recording was done at Sun Studio, Memphis, on July 30, 1955, with Sam Phillips producing. Cash was backed by Luther Perkins (guitar) and Marshall Grant (bass), together known as The Tennessee Two. The stripped-down setting, without drums, underlines the rawness, the urgency and loneliness of the piece.

While the studio version made waves on country charts in the mid-50s, “Folsom Prison Blues” perhaps had its greatest resurgence over a decade later. On January 13, 1968, Cash performed a concert in California’s Folsom State Prison, recording the live show for the album At Folsom Prison. That live version became a major hit: it reached #1 on the US country charts and cracked into the Billboard Hot 100, rising to #32 in 1968.

The song stands not just as a reflection of prison life, but as a metaphor. Freedom is always just out of reach. The whistle of a train represents both escape and impossibility. Guilt and regret haunt the speaker, not simply for what he’s done, but for what he has lost: freedom, time, innocence. These feelings resonate especially with listeners who’ve known loss, seclusion — or who have watched their own world slip through fingers in small ways.

Johnny Cash didn’t need to have lived behind bars to speak for those who did. Through empathy, voice, and longing, he inhabited that space. And because of that, “Folsom Prison Blues” remains timeless — a song that older listeners remember in crackling records, in live performances, in the steady approach of that imaginary train whistle.