Swaggering hymn to bravado and bluff, where youthful confidence masks the hunger to be seen and believed.

When Brian Connolly, as the unmistakable voice of Sweet, released Poppa Joe in 1972, the single climbed to a strong No. 11 on the UK Singles Chart, consolidating the band’s early momentum in the British pop landscape. It was drawn from Funny How Sweet Co-Co Can Be, an album that captured Sweet at a formative moment, poised between bubblegum immediacy and the harder edged glam authority they would soon command. In chart terms, Poppa Joe did not yet signal superstardom, but it confirmed a presence, a sound, and a frontman whose delivery gave theatrical weight to even the most playful material.

At first glance, Poppa Joe announces itself with a strut. The groove is jaunty, the chorus insistent, the persona outsized. Yet beneath the surface bravado lies a carefully constructed character study. The song introduces Poppa Joe as a figure of exaggerated self belief, a man who talks big, dresses loud, and sells an image of success that may or may not be real. This ambiguity is the song’s quiet genius. It never collapses the illusion. Instead, it lets the listener sit with the tension between confidence and insecurity, between performance and truth.

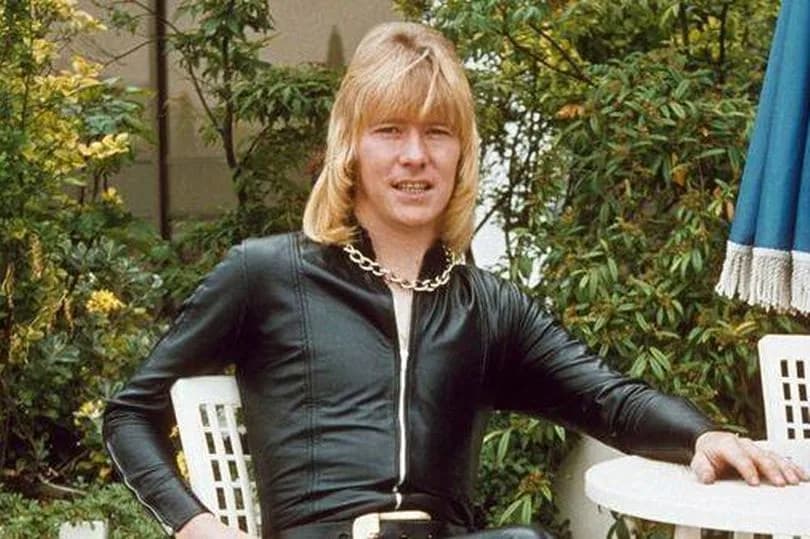

Much of that tension is carried by Brian Connolly’s vocal performance. Connolly sings with a knowing wink, stretching syllables, leaning into phrasing that suggests both admiration and mockery. His voice elevates the lyric from novelty to narrative. Poppa Joe becomes less a cartoon and more a mirror, reflecting a universal impulse to invent oneself louder than life. In the early 1970s, as glam rock began celebrating artifice as identity, this theme resonated deeply. Image was currency. Style was armor. Poppa Joe understands this instinctively, even if he is also trapped by it.

Musically, the track sits comfortably in the Chinn and Chapman production lineage, tight rhythms, handclaps, and a chorus engineered for instant recall. Yet it avoids emptiness. The repetition becomes ritualistic, reinforcing Poppa Joe’s self mythologizing. Each refrain sounds like a mantra he repeats to keep doubt at bay. The music does not judge him. It dances alongside him.

Culturally, Poppa Joe occupies an important place in Sweet’s evolution. It bridges their early pop accessibility with the more assertive glam anthems that would follow. For Connolly, it is an early showcase of the charisma that made him indispensable. His ability to inhabit a character, to suggest layers beneath a bright surface, is already fully formed here.

Listening now, decades removed from its chart run, Poppa Joe endures not because it promised depth, but because it delivered something subtler. It captured the sound of a young scene learning how to perform itself into existence. It reminds us that behind every loud declaration of success is a quiet plea to be noticed, remembered, and believed. In that sense, Poppa Joe never really left. He just learned to smile wider.