A ferocious celebration of freedom where rebellion becomes rhythm and confinement turns into dance.

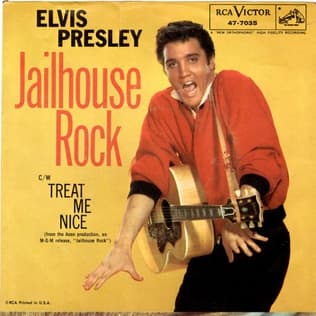

When Elvis Presley released Jailhouse Rock in 1957, the impact was immediate and overwhelming. Issued as a single and as the title track of the soundtrack EP Jailhouse Rock, the song surged to number one on the Billboard Top 100, holding the position for seven consecutive weeks, while also topping charts internationally. For a popular artist already reshaping the sound and posture of American music, this record marked a moment where commercial dominance and cultural provocation aligned with rare precision.

Written by the formidable songwriting team of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, Jailhouse Rock distills rock and roll to its most combustible elements. It is built on a lean, stomping rhythm, a snarling guitar figure, and a vocal performance that feels half sung, half sneered. Presley does not merely narrate the scene of a prison dance. He inhabits it, turning incarceration into spectacle and authority into something to be mocked, teased, and ultimately overtaken by movement. The lyrics introduce a gallery of characters with cartoon sharpness, each name landing like a punchline, yet beneath the humor lies a deeper inversion. This is a song where the locked up are liberated through sound, and the walls themselves seem to vibrate in surrender.

The recording is famously tight, almost claustrophobic, which only intensifies its effect. Scotty Moore’s guitar snaps and coils rather than solos. The rhythm section moves with disciplined aggression, echoing the regimented environment described in the song, while Presley’s voice strains against it, bending notes with a physical urgency that suggests escape rather than compliance. Rock and roll here is not decorative. It is defiant. It refuses polish. It thrives on friction.

Beyond the studio, Jailhouse Rock became inseparable from its visual legacy. The performance sequence in the 1957 film cemented Presley’s image as both dancer and provocateur, translating sound into a language of sharp angles and sudden stillness. For many viewers, this was not simply entertainment. It was a rupture. The song’s success signaled that youth culture no longer needed permission, nor refinement, to dominate the mainstream.

What endures about Jailhouse Rock is not novelty or nostalgia, but clarity of intent. It captures rock and roll at the moment it understood its own power. There is no moral lesson offered, no redemption arc imposed. Instead, the song insists that joy itself can be an act of resistance. In the echo of handclaps and the stomp of a backbeat, confinement dissolves. What remains is motion, sweat, and the sound of a culture kicking against the door and laughing as it does so.