A Tragic Trail, A Timeless Lament: The Ballad of the Little Lost Soul

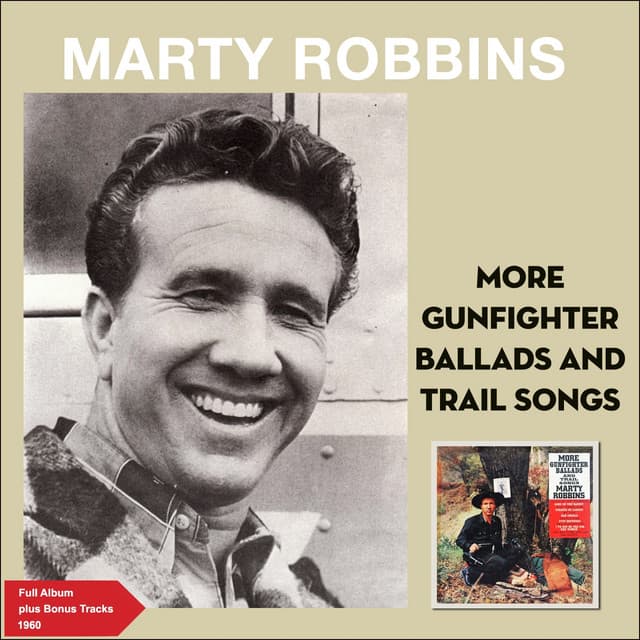

When we speak of the golden age of Western music, the name Marty Robbins looms as large as a lone butte on the horizon. His voice, a soothing, crystalline stream flowing over the hardscrabble realities of the frontier, gave a genuine soul to the Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs—stories that echo the very foundation of American myth. Among those enduring sagas, his 1960 recording of “Little Joe the Wrangler,” featured on his essential second album of Western material, More Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs, stands out.

It is crucial to note at the outset that Marty Robbins’ version of “Little Joe the Wrangler” was a deep cut from a themed album, not a standalone single intended for the fast-moving country or pop charts, unlike his mammoth hits like “El Paso.” Consequently, this masterful recording did not register on the major Billboard Country Singles or Hot 100 charts at the time of its release. Its stature is instead measured by its enduring presence in the hearts of Western music aficionados and its role as a cornerstone of one of the most beloved cowboy albums ever recorded. Robbins was a profound champion of the Western genre, and this track, long beloved, found its home on the radio waves and turntables through the immense popularity of the album itself, an album which peaked at No. 20 on the Billboard Top LPs chart in the era of its release.

The Enduring Story and Deep Meaning

The true genius and emotional core of “Little Joe the Wrangler” is that it is not merely a song, but an American folk ballad. Its origins trace back to the pen of a real cowboy, N. Howard “Jack” Thorp, who wrote it while trailing cattle in 1898 and published it in his seminal 1908 collection, Songs of the Cowboys. Marty Robbins wasn’t crafting a new pop song; he was respectfully interpreting a vital piece of authentic trail history.

The story is simple, stark, and utterly heart-wrenching. It recounts the arrival of “Little Joe,” a young, tough-looking Texas stray, riding a pony called “Chaw.” He’s a runaway, a child fleeing a new stepfather’s cruelty. The trail boss, seeing the boy’s earnest desire to paddle his “own canoe,” takes him on as a horse wrangler. Little Joe finds a brief, hard-won family amongst the rough-hewn men of the cattle drive, a surrogate home where a boy can do a man’s job. The song’s profound meaning rests in this moment of acceptance and the crushing tragedy that follows. When a terrifying “norther” blows in and the herd stampedes, it is Little Joe, the least among them, who is seen “tryin’ to check those cattle in the lead.” He rides bravely into the chaos, only to be found the next morning, crushed beneath his horse in a washout.

For those of us who grew up on these tales, this ballad hits a raw nerve. It’s a testament to the courage of the forgotten, the small, lost souls who had to grow up too fast and paid the ultimate price for a piece of self-respect. It evokes a powerful sense of nostalgia, not just for the music, but for a simpler, albeit more brutal, time when a man’s word and a boy’s mettle were all that mattered.

Robbins’ Reflective Delivery

Marty Robbins‘ gift was his ability to treat these narratives with a quiet dignity that amplified their sorrow. He doesn’t belt the song; he tells it, like a grizzled cowhand recounting a memory by a dying campfire. His version, like all true classics, has a timeless, meditative quality, drawing on the melody of the older song “Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane.” It captures the fleeting, beautiful tragedy of the trail—the immense, empty landscape that could offer freedom in one breath and death in the next. Listening to it now, decades later, you can almost smell the dust and the rain, and feel the cold knot of grief for the “little Texas stray” who will “wrangle nevermore.” It’s a reminder that beneath the adventure and romance of the West lay real, vulnerable human beings, and some stories simply don’t get a happy ending.