A nocturnal confession where longing turns sleep into a fragile refuge and dreams become the only place love still answers back.

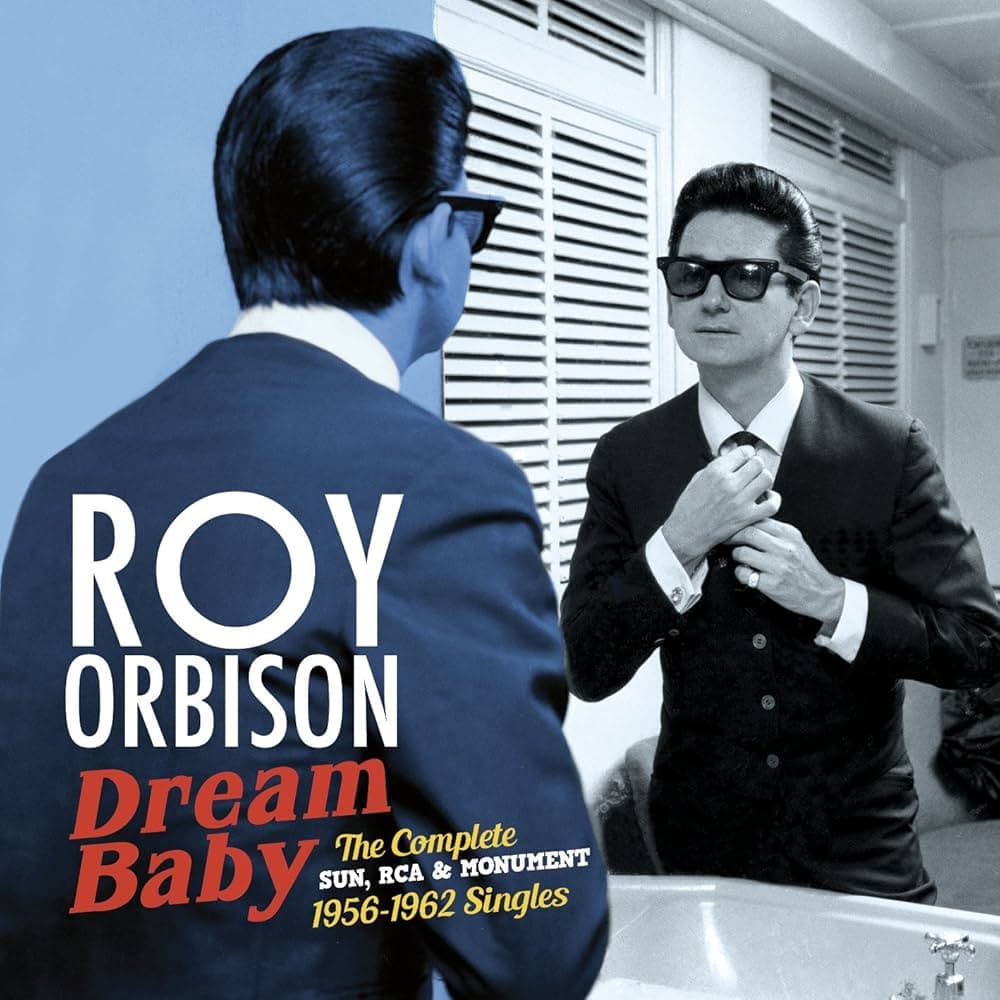

Released in 1962, DREAM BABY arrived as one of ROY ORBISON’s most quietly devastating hits, climbing to No. 4 on the Billboard Hot 100 and confirming his singular command of emotional pop at the dawn of the decade. The song later found its permanent home on IN DREAMS, the 1963 album that framed Orbison’s voice as a vessel for romantic vulnerability and operatic restraint. By the time listeners placed the needle down, it was clear that this was not simply another chart success but a continuation of an unfolding emotional canon that few singers could inhabit with such authority.

At first glance, DREAM BABY presents itself with deceptive simplicity. The melody is gentle, almost lulling, built on a rocking rhythm that mirrors the act of falling asleep. Yet beneath that calm surface lies one of Orbison’s most intimate emotional scenarios. The narrator is not pleading in daylight or arguing in the aftermath of betrayal. He is alone, awake, suspended in the quiet hours where memory grows louder and hope becomes a whispered wish. Sleep is not escape here. It is the only remaining meeting place where love might still exist, untouched by reality.

Orbison’s genius lies in how he transforms yearning into structure. The song does not rush toward catharsis. Instead, it circles the same ache repeatedly, each verse reinforcing the idea that desire has nowhere left to go but inward. Dreams are portrayed not as fantasy but as necessity, a final sanctuary when waking life has closed its doors. The restraint in the arrangement amplifies this effect. Strings hover rather than soar. The rhythm section keeps time like a heartbeat that refuses to accelerate. Everything serves the voice.

And what a voice it is. Orbison sings not with bravado but with a kind of exposed dignity. His phrasing stretches certain syllables just long enough to suggest hesitation, as if even speaking the desire aloud might break it. When he reaches upward in the chorus, the ascent feels less like triumph and more like reaching for something that may no longer be there. This emotional ambiguity is central to the song’s power. It never tells the listener whether the love is lost, distant, or simply unreturned. It only tells us that it is absent now.

Culturally, DREAM BABY stands as a bridge between eras. It carries the innocence of early 1960s pop while foreshadowing the deeper emotional introspection that would soon dominate songwriting. Its influence can be heard in later artists who explored vulnerability without irony, who trusted quiet confession over spectacle. That is why the song endures. It does not age because longing does not age.

In the end, DREAM BABY is not about sleep at all. It is about what remains when everything else has gone quiet. In that silence, Roy Orbison invites the listener to sit with longing, not to resolve it, but to honor it. The record spins, the night deepens, and somewhere between memory and imagination, love still answers, if only in a dream.