A solitary voice drifts through the darkness, turning the quiet hours of the night into a confession of longing that refuses to fade.

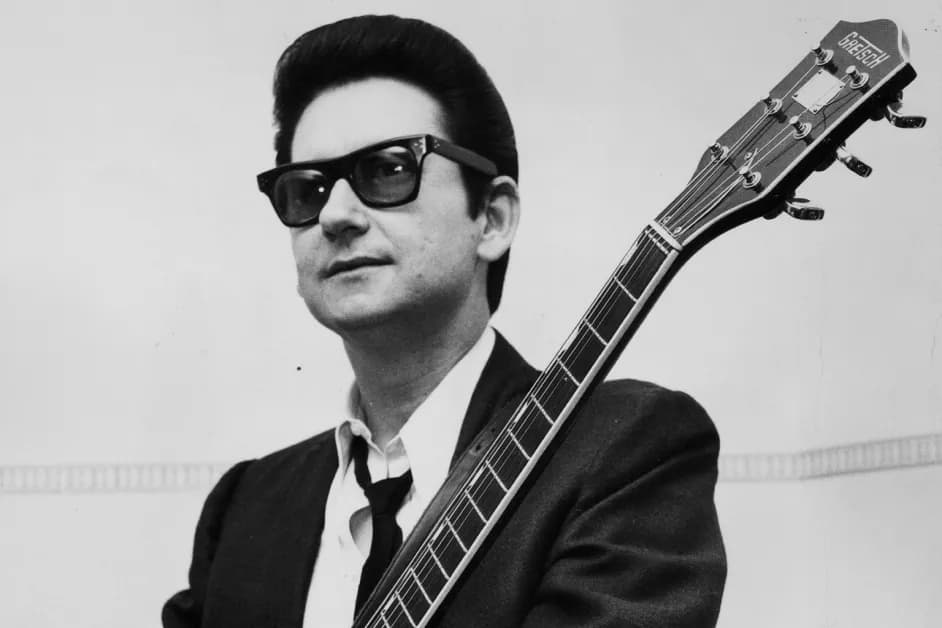

In the long arc of American popular music, few voices carry the spectral intensity of Roy Orbison, and his rendition of Night Life stands as a testament to his singular ability to inhabit a song until it feels carved from his own experience. Originally written by Willie Nelson and embraced by generations of country and blues artists, the piece found a new resonance when Orbison recorded it during his early 1960s period, an era when his work was defined by sweeping emotional ambition and an increasingly cinematic vocal style. While the track was not positioned as a chart contender in the same way as Orbison’s major hits of the time, it circulated within the same creative orbit that produced some of his most acclaimed recordings. The song appeared on releases that showcased his interpretive depth, placing it alongside material that emphasized both his range and his uncanny ability to turn a lyric into a moment suspended between vulnerability and command.

The deeper story of Night Life has always been embedded in its writing. Nelson’s lyric sketches the world after midnight, when neon light falls across empty streets and confessions come easier. What Orbison brings is a voice that seems built for these hours. His delivery stretches the melody until it feels like a slow exhale, a release of tension that keeps tightening even as it unfolds. He does not dramatize the loneliness at the heart of the lyric. Instead, he illuminates it. The night becomes a companion, the silence a witness, and the wandering figure at the center of the song becomes a reflection of anyone who has walked through late hours searching for a place to let their thoughts settle.

Where other interpretations highlight grit or resignation, Orbison leans into atmosphere and shadow. His phrasing creates long corridors of sound, letting each line hover with a kind of delicate ache. The arrangement supports him with subtlety, inviting the listener into a space that is less a barroom than a dreamscape shaped by soft electric guitar and patient rhythm. In this setting, the familiar declaration that the night life is not a good life becomes less a warning and more an acknowledgment of a truth many understand but rarely articulate. Orbison makes the line feel lived in, as if each word had been carried for miles before reaching the microphone.

The cultural legacy of Night Life endures because the song captures a universal sensation. It is the sound of the world when crowds disperse and the lights dim, when introspection rises and memory becomes sharper. Orbison’s interpretation adds another layer to this lineage. He turns the lyric inward, tracing the contours of solitude until it becomes almost luminous. In doing so, he affirms that the night is more than a time of day. It is a landscape of feeling, a place where the heart speaks plainly.