A lonely joker painted in shadows and applause

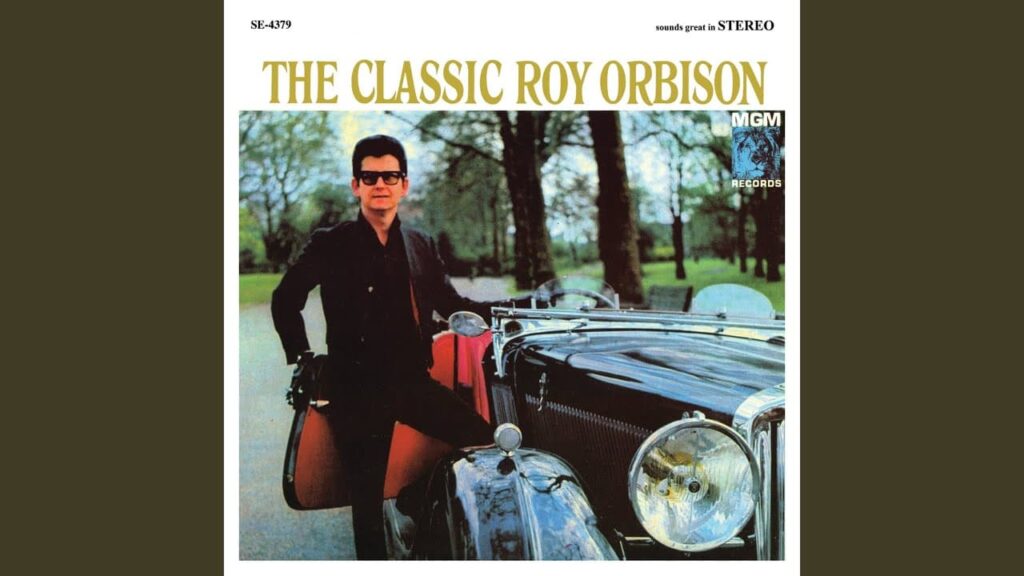

Pantomime, by Roy Orbison, appears on the 1966 album The Classic Roy Orbison. While the song itself was never released as a major hit single and therefore lacks the chart-topping pedigree of Orbison’s more famous works, it occupies a striking place among the songs from his MGM Years — a period when he continued to channel heartbreak into elegiac melodies and emotional subtlety.

In the mid-1960s, after a string of iconic hits that cemented his reputation as one of rock’s most expressive voices, Orbison and longtime collaborator Bill Dees wrote and recorded a batch of songs that veered away from the bombast of his chart-toppers and stepped deeper into introspection and vulnerability. The sessions that produced The Classic Roy Orbison were completed mere months before a personal tragedy — the death of his wife — a fact that retroactively casts many of the album’s songs, including Pantomime, in a more haunting light.

At first listen, Pantomime may seem deceptively carefree: its tempo moves with steady confidence — around 120 BPM — giving it a rhythmic backbone that almost suggests a jaunty swagger. But the lyrics undercut the surface cheer. The narrator describes himself as “the king of the clowns,” a lonely joker whose laughter is thin and brittle, masking the ache of unrequited love. He drinks, parties, and laughs — yet privately he cries inside because the one he longs for is not his. “You are not mine so I waste my time in pantomime,” he confesses.

That tension — between appearance and truth, joy and anguish — is quintessential Orbison. Though not one of his grand, operatic ballads, Pantomime exemplifies his uncanny ability to musically inhabit the spaces where the heart hides; to make grief dance, and to make sorrow sing. The musical arrangement does not overwhelm. Instead, it supports. The steady beat and measured pace enact the rhythm of someone trying to keep moving forward — to hide the pain behind movement, noise, company. Yet every note seems weighted, every line fragile.

In the broader arc of Orbison’s career, Pantomime stands as a quiet testament to his evolving artistry. It is not a song built for radio domination or chart metrics. Rather, it is a documentary of inner turmoil: a confession in the middle of a crowded room, a sliver of honesty carved out beneath pop glamour. For listeners attuned to nuance — those who appreciate the spaces between the notes, the shadows behind the spotlight — Pantomime is deeply resonant. Its legacy lies not in commercial success but in emotional truth.

Listening to Pantomime decades after its recording, one hears more than a lonely man trying to distract himself. One hears the ache of longing, the masquerade of joy, the painful grace of someone caught between loving and letting go. In that space, Roy Orbison reveals not just a voice — but a soul.