Portrait of quiet devotion, where love accepts its lesser place and endures anyway

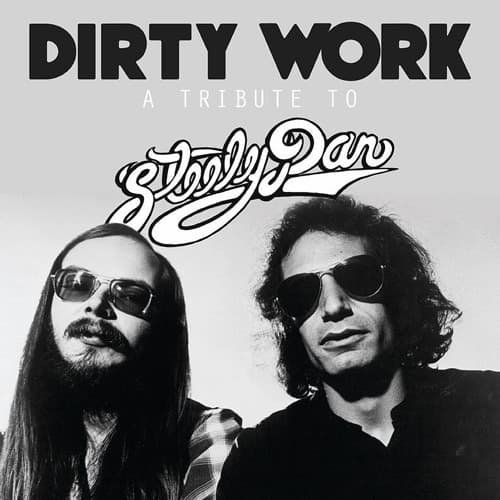

When Steely Dan released Dirty Work in 1972 on their debut album Can’t Buy a Thrill, the song rose to No. 11 on the Billboard Hot 100, announcing the band not only as sharp musical craftsmen but as observers of emotional complexity well beyond typical pop confession. Sung by David Palmer rather than Donald Fagen, Dirty Work occupies a singular place in the Steely Dan catalog, both commercially and emotionally. It was a hit that did not rely on bravado or romantic triumph, but on resignation, restraint, and an honesty that feels almost uncomfortable in its calm acceptance.

At its core, Dirty Work is a song about complicity. Not betrayal in the loud, dramatic sense, but the quieter, more corrosive kind where one willingly steps into the shadows of someone else’s life. The narrator understands the imbalance from the opening lines. There is no illusion of permanence, no promise of rescue. Instead, there is a sober acknowledgment of role and limitation. This voice does not demand, does not plead, and crucially, does not absolve itself. It agrees to remain secondary, hidden, necessary but never chosen.

Musically, Dirty Work reinforces this emotional posture with remarkable subtlety. The chord progression drifts with a soft inevitability, guided by a gentle electric piano and understated rhythm section. There is no urgency in the arrangement. The groove settles into a steady, almost comforting pace, mirroring the narrator’s decision to accept the terms as they are. Larry Carlton’s guitar work adds a restrained elegance, never intruding, always serving the song’s inward gaze. This is Steely Dan at their most deceptively accessible, disguising moral ambiguity beneath polished harmonies.

Lyrically, Becker and Fagen avoid judgment. The song never condemns the lover who asks for secrecy, nor does it romanticize the sacrifice. Instead, it documents a psychological space many listeners recognize but rarely articulate. The willingness to accept less than dignity in exchange for proximity. The fear that refusal would mean erasure. Lines unfold like private admissions rather than public statements, and that intimacy is precisely why the song endures. It does not instruct. It observes.

Within the broader context of Can’t Buy a Thrill, Dirty Work stands apart. While other tracks introduce Steely Dan’s sardonic wit and jazz informed sophistication, this song leans toward vulnerability. It hints at the thematic direction Becker and Fagen would later pursue more obliquely, examining flawed characters who understand their compromises all too well. Here, that understanding is still tender, not yet armored with irony.

Over time, Dirty Work has grown beyond its chart success into a cultural touchstone for listeners drawn to its emotional candor. It remains one of Steely Dan’s most covered songs, perhaps because it invites singers to inhabit its quiet surrender. The song does not age because the situation it describes does not. As long as people choose closeness over self respect, Dirty Work will continue to feel uncomfortably familiar, a polished mirror held up to the softer failures of the heart.