A confession of restless sorrow that accepts loneliness as both wound and companion

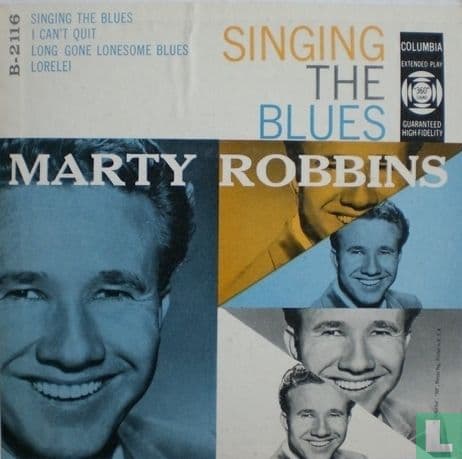

Released as an album cut rather than a chart-seeking single, Long Gone Lonesome Blues appears on Songs of Hank Williams, the 1956 tribute album recorded by Marty Robbins, a project that placed him in direct dialogue with the emotional bedrock of postwar country music. While this recording did not arrive on the charts as a standalone hit, its significance rests elsewhere, in the way Marty Robbins approached a song already etched into the collective memory and chose reverence over reinvention, restraint over spectacle.

At its core, Long Gone Lonesome Blues is not merely about heartbreak. It is about the permanence of emotional displacement, the quiet recognition that some forms of loneliness do not resolve, they simply settle in. The narrator does not dramatize his pain or plead for sympathy. Instead, he reports it with weary clarity, as though solitude has become an accepted condition of life. This emotional economy is the song’s greatest strength, and it is precisely what Marty Robbins understood when he stepped into its lines.

Robbins was never an imitator by instinct. Even when paying tribute, he filtered material through his own vocal discipline and moral seriousness. On Songs of Hank Williams, he resisted the temptation to mimic Williams’ raw edge. Instead, Robbins offered a smoother, steadier delivery that reframed the song as reflection rather than confession. His voice carries dignity, suggesting a man who has survived his sorrow long enough to speak of it without trembling, yet not long enough to forget its weight.

Lyrically, the song operates on simple imagery that conceals deeper resignation. Trains, distance, and emotional abandonment are not metaphors of drama here but of inevitability. The narrator is not shocked by loss. He expects it. This expectation transforms the song from a lament into a philosophy of endurance. In Robbins’ hands, that philosophy becomes almost stoic. Each line lands gently, as if he is careful not to disturb the fragile balance he has built around his grief.

Musically, the arrangement remains faithful to traditional country structure, allowing melody and narrative to move in tandem. There is no ornamental excess, no flourish designed to distract from the truth being spoken. Robbins’ phrasing elongates certain syllables just enough to suggest reflection, the sound of a man thinking aloud rather than performing for an audience.

Within the broader context of Marty Robbins’ career, this recording reveals an artist deeply aware of lineage. By including Long Gone Lonesome Blues on Songs of Hank Williams, Robbins acknowledged the emotional grammar that shaped modern country music while quietly asserting his own interpretive authority. He did not attempt to replace the song’s origin. He preserved it, framed it, and allowed it to speak through a different emotional lens.

Today, Robbins’ version stands as a reminder that some songs endure not because they change with time, but because each generation finds a new voice willing to tell the same hard truth with honesty. Long Gone Lonesome Blues remains a song about learning how to live with absence, and in Marty Robbins, it found a narrator who understood that survival itself can be a form of quiet courage.