Ballad Where Honor, Obsession, and Fate Collide Beneath a West Texas Sky

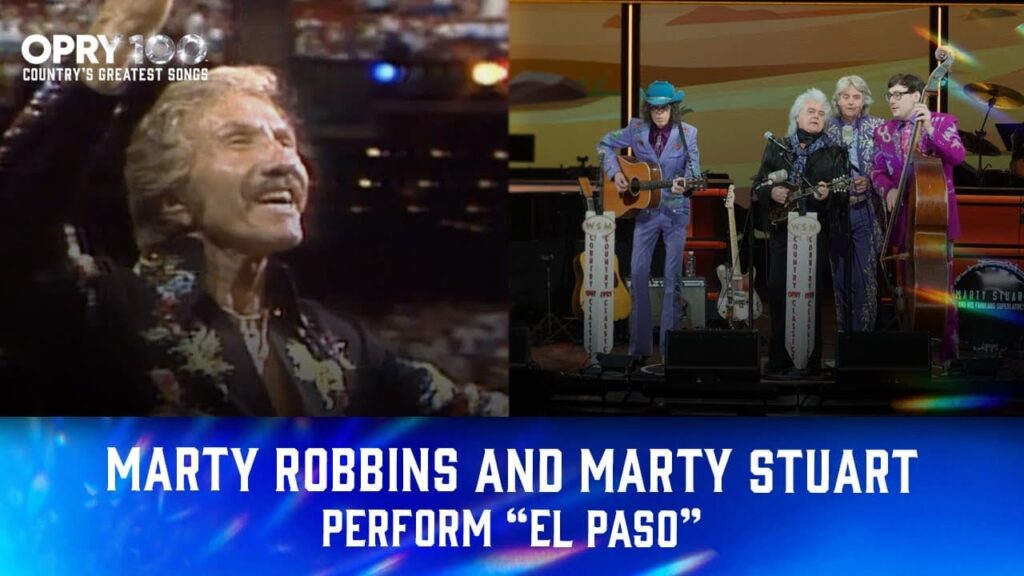

When Marty Robbins released “El Paso” in 1959 as part of his landmark album Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs, few could have predicted that a four-minute Western epic would gallop to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 and the Country chart alike. It was an anomaly in an era leaning toward brevity, yet its sweeping narrative and cinematic scope felt defiantly unhurried. Decades later, when Marty Stuart joined the lineage at the Grand Ole Opry celebration, revisiting the song for Opry 100: Country’s Greatest Songs, it was less a cover than a ceremonial passing of the torch, an acknowledgment that some ballads are not merely sung, but stewarded.

At its heart, “El Paso” is a tragedy told with the moral clarity of an old Western and the emotional ambiguity of a Greek drama. Robbins did not simply write a song; he constructed a frontier novella in verse. The jealous lover, the fatal gunfight, the exile in the badlands of New Mexico, and the irresistible pull back to the arms of Felina—each element unfolds with deliberate pacing. The melody, carried by that distinctive Spanish-tinged guitar figure, establishes geography before the first line has fully settled. One can almost feel the adobe dust rising.

What distinguishes “El Paso” is its refusal to romanticize consequence. The narrator kills for love, flees for survival, and returns for longing. His fate is sealed not by villainy but by devotion. “One little kiss and Felina, goodbye.” In that final line lies the song’s enduring ache. Robbins understood that the Western myth is built on both valor and vulnerability. The ballad lingers not on the gunshot, but on the stillness afterward.

Musically, Robbins’ phrasing is deceptively restrained. He sings not as a swaggering gunslinger, but as a reflective man already haunted by his own decisions. The spacious production allows the narrative to breathe; there is room between the notes, as wide as the Texas desert itself. That sense of scale made the record feel epic without resorting to bombast.

When Marty Stuart revisits the song in the Opry’s centennial tribute, he approaches it with reverence, preserving the cadence and melodic contours that Robbins etched into country music’s canon. Stuart’s interpretation underscores the song’s status as communal heritage. It reminds us that “El Paso” is not merely a period piece, but a living document of country storytelling at its most ambitious.

In an industry often defined by fleeting hits, “El Paso” stands as proof that narrative daring can triumph commercially and artistically. It remains one of country music’s most vivid portraits of love entangled with destiny, a ballad that rides on long after the final chord fades.