A Tear-Stained Souvenir of Home: The Enduring Longing of “Blue Bayou”

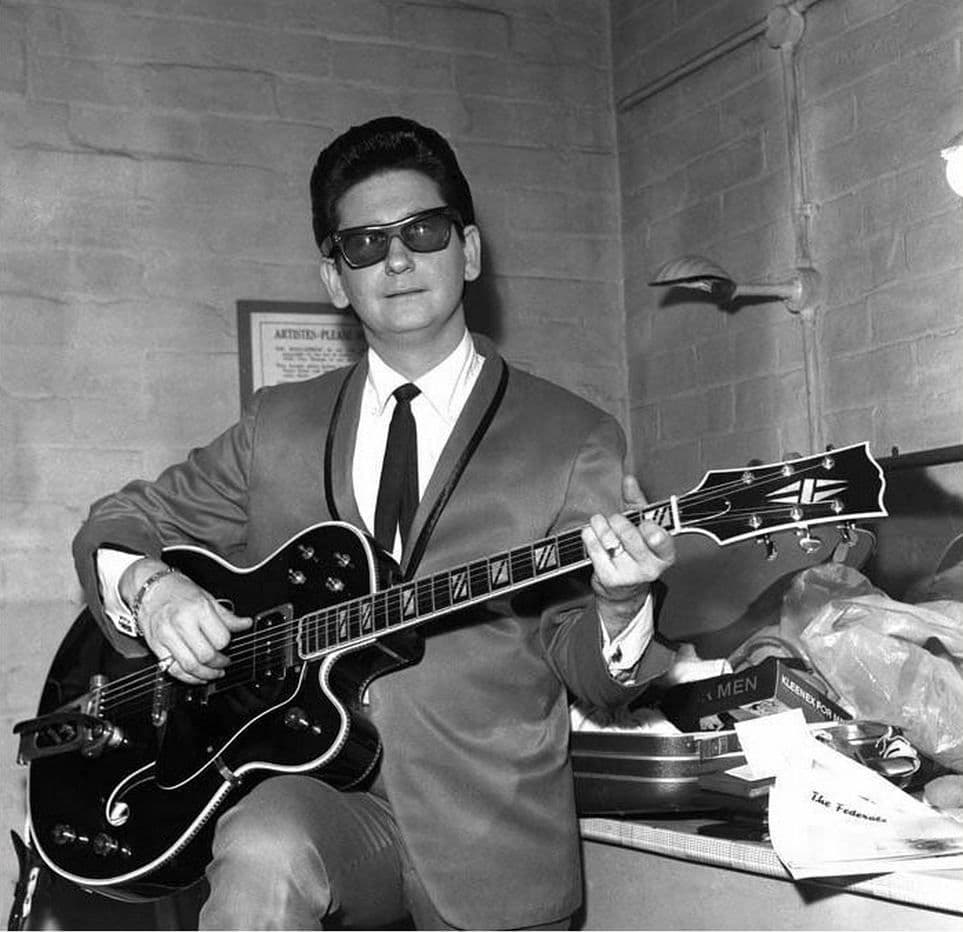

There are certain songs that don’t just occupy a space on the radio dial; they become permanent residents in the chambers of memory, carrying the bittersweet scent of a life long past. Roy Orbison’s 1963 classic, “Blue Bayou,” is one such immortal tune, a masterpiece of yearning delivered by a voice that seemed to contain all the world’s sorrow. Released as the flip-side to his bigger U.S. hit, “Mean Woman Blues,” this gorgeous, wistful ballad nonetheless found substantial international success. While it only peaked modestly at No. 29 on the Billboard Hot 100 upon its August 1963 release, its reach was profound: it climbed to a soaring No. 3 in the UK and even hit No. 1 in Australia and Ireland. The song was featured on his classic album, In Dreams, a 1963 release that cemented the Texas-born singer’s reputation as a purveyor of operatic rock and roll emotion.

The story behind “Blue Bayou” is one of simple, yet universal, heartbreak. Co-written by Orbison and his frequent collaborator, Joe Melson (who also co-wrote hits like “Only the Lonely” and “Crying”), the song emerged from an inkling of an idea that took root on a road trip from Arkansas back home to Texas. It’s a beautifully concise narrative about a person who has left their home—specifically a tranquil bayou—to chase an uncertain future, presumably seeking a better living, “Saving nickels, saving dimes, working ’til the sun don’t shine.” The lyrics are a heartfelt lament from a place of loneliness and exhaustion, looking forward only to the day they can afford to go back. The bayou itself is a potent symbol—it’s not just a location, but the very embodiment of peace, belonging, and an uncomplicated love: “Where you sleep all day and the catfish play.” The narrator’s desperation is palpable in the repeated refrain: “I’m going back someday, come what may, to Blue Bayou.”

What sets Orbison’s version apart and gives it its reflective power is the dramatic, almost cinematic quality of his voice—the famous three-octave range that made him “The Big O.” His vocal performance here is less the soaring agony of “Crying” and more a soft, persistent ache. It’s a gentle, rocking tempo, punctuated by the classic ’60s pop harmonies and a surprisingly fluid, almost haunting use of the harmonica. This instrumentation creates an atmosphere of deep, blue-tinged nostalgia, making it perfect for those of us who carry the weight of distant youth or a cherished place we can’t quite return to. The emotion is raw but contained, like a tear shed for a memory that’s too beautiful to be truly sad.

Interestingly, for many younger listeners, or those who came to music a bit later, “Blue Bayou” is inextricably linked to the phenomenal 1977 cover by Linda Ronstadt, which took the song to even greater heights in the U.S., becoming her signature track and reaching No. 3 on the Billboard Hot 100. While Ronstadt’s rendition is a gorgeous, sun-drenched, and vocally acrobatic take, Orbison’s original holds a quiet, somber strength. His version remains the essential recording for those who remember when the song was simply an emotional B-side, a profound reflection on the universal human condition of longing for home, for lost innocence, and for the simplicity of a love left behind—a true tear-stained souvenir of a faraway paradise. It’s a song for anyone who’s ever had to leave something wonderful to find something necessary, only to discover that the heart was left behind on the banks of their own Blue Bayou.