A rock and roll invocation where youthful abandon meets seasoned reflection

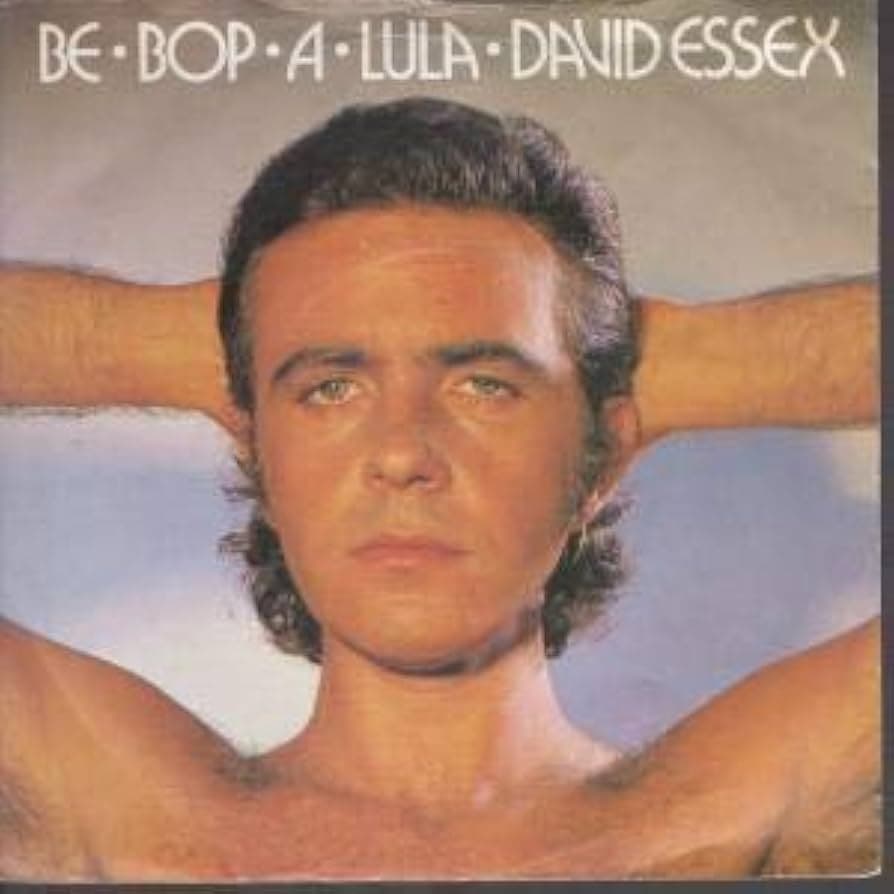

Released as a charting UK single by David Essex during the late nineteen seventies, Be-Bop-A-Lula stands as both a reverent nod to rock and roll’s primal language and a statement of artistic lineage. Recorded by David Essex and issued as a standalone single that later lived on through compilations, the track connected with the UK Singles Chart on release, reaffirming Essex’s instinct for translating American rock mythology into a distinctly British emotional register. Though forever linked to its original incarnation, Essex’s version arrived at a moment when nostalgia was no longer escapism but reflection.

To understand Be-Bop-A-Lula in Essex’s hands is to understand the song not as novelty or revivalism, but as inheritance. Written and first immortalized by Gene Vincent in 1956, the song had already become a cornerstone of early rock and roll vocabulary. Its lyrics were never about narrative precision. They were about sensation, rhythm, desire rendered as sound. Essex approaches this material not as an imitator but as a custodian. His vocal carries weight, a trace of lived experience that subtly alters the song’s emotional gravity. Where Vincent sounded like rebellion breaking loose, Essex sounds like memory returning with clarity.

Musically, Essex resists overproduction. The arrangement preserves the essential drive of the original, its swinging pulse and loose-limbed confidence, but tempers it with polish that reflects the era in which it was reintroduced. The guitar lines remain taut and insistent, the rhythm section keeps the song moving forward without urgency, and Essex’s vocal phrasing leans into control rather than raw eruption. This restraint is crucial. It allows the song’s charm to emerge not as adolescent bravado, but as something closer to affection and respect.

Lyrically, Be-Bop-A-Lula has always functioned as an incantation rather than a story. The repetition, the playful syllables, the breathless admiration all operate on a level beneath logic. In Essex’s performance, these elements take on a reflective quality. The words feel less like discovery and more like remembrance. There is an unspoken awareness that this language once changed everything, that it cracked open a future where emotion could be shouted, sung, and shaken loose from convention.

Culturally, Essex’s version arrives as a bridge between generations. By the time of its release, rock and roll had already fractured into countless forms, some louder, some more cynical. Returning to Be-Bop-A-Lula was not regression. It was acknowledgment. Essex understood that the song’s power lay not in modernizing it, but in letting it stand as evidence of where everything began. His interpretation invites the listener to hear the song not as an artifact, but as a living pulse that continues to echo.

In the end, Be-Bop-A-Lula as performed by David Essex is less about revival than continuity. It reminds us that rock and roll does not age, it accumulates meaning. Each voice that carries it forward adds another layer of memory, another reason the rhythm still matters.